9-month-old boy with congenital lung abnormality

Case summary

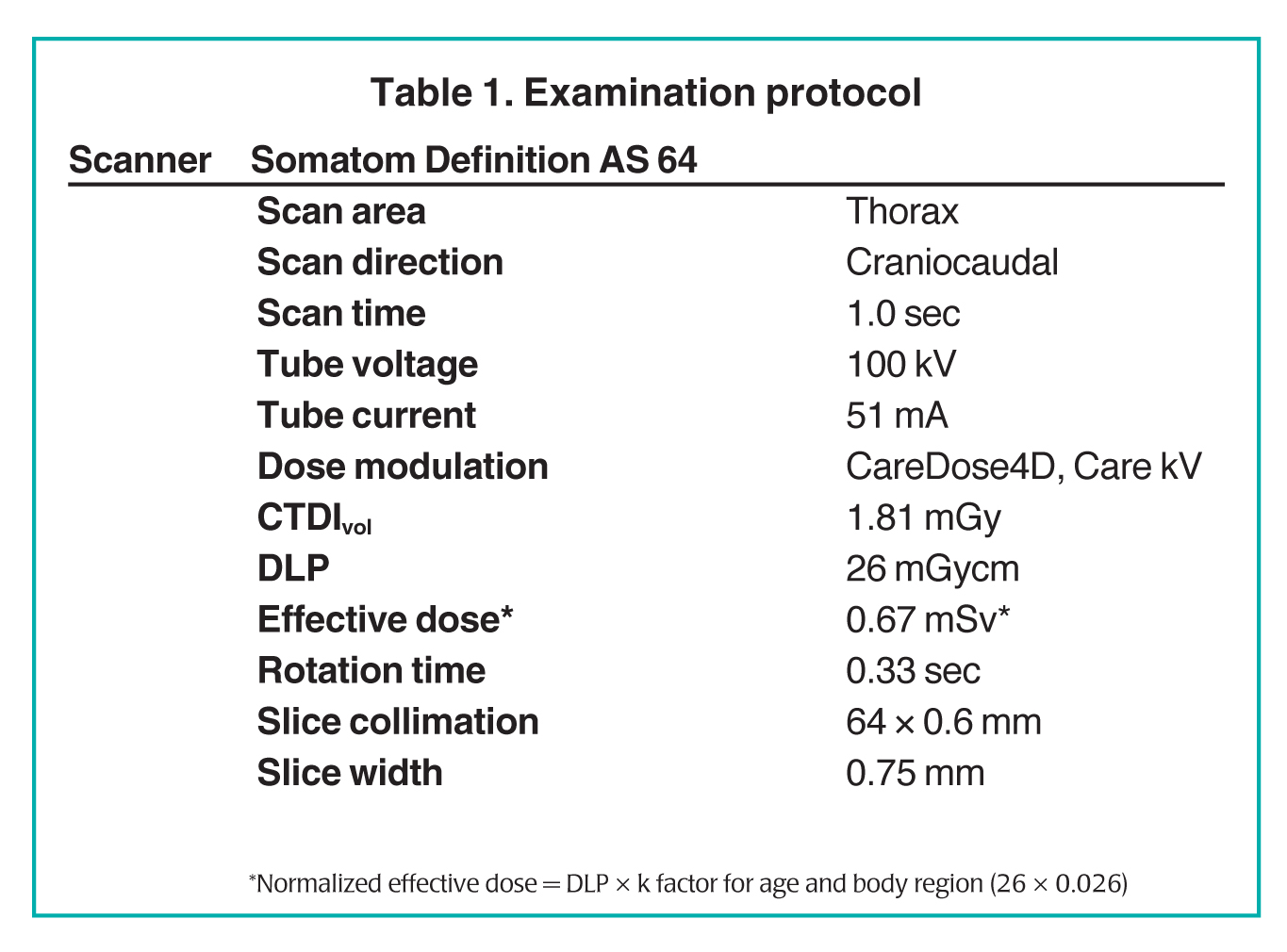

A 9-month-old boy presented for follow-up of a “congenital lung abnormality” detected in utero. The patient was asymptomatic. Because the nature of the underlying lung abnormality was not clear from the in utero ultrasound or postnatal chest radiography, low-dose computed tomography (CT) was performed.

Imaging findings

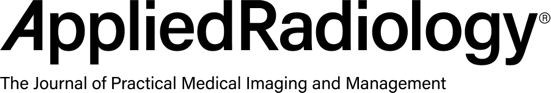

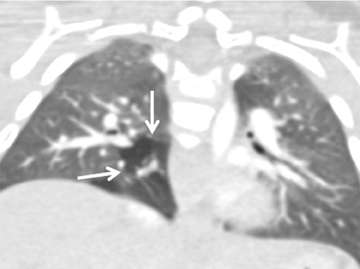

In Figure 1, axial (A) and multiplanar coronal (B) and sagittal (C) lung-window CT images show a branching, tubular structure, consistent with a mucoid-filled segmental right lower-lobe bronchus, surrounded by hyperlucent lung parenchyma (arrows), indicating associated overinflation. The CT features are diagnostic of bronchial atresia.

Diagnosis

Congenital bronchial atresia; right lower lobe

Discussion

Bronchial atresia is a congenital anomaly of unknown etiology, in which a segmental bronchus fails to communicate with the central airways. Its etiology is unknown, but one hypothesis is that it is a sequela of vascular insult to the lung parenchyma at approximately 16 weeks of gestation.1 Another theory is that bronchial atresia is the result of separation of the bronchial bud from the airway during the 5th to 6th week of gestation. This may explain why bronchial atresia can coexist with pulmonary sequestration and bronchogenic cysts, which also develop during this time period. It most commonly affects the apical-posterior segment of the left upper lobe, although other lobes can be involved.

Gross inspection shows a proximal blind-ending bronchus and dilated distal segmental bronchi plugged by mucus with adjacent hyperinflated lung parenchyma. Microscopic analysis reveals enlarged alveoli, corresponding to the finding of hyperinflation, and mucoid impaction of the bronchus distal to the site of atresia.2 Destructive changes in the alveolar walls are unusual, unlike the destruction seen in emphysema. Distal overinflation is believed to be caused by collateral ventilation through intraalveolar pores of Kohn, bronchoalveolar channels of Lambert, and/or interbronchiolar channels, which connect terminal bronchioles in adjacent lung segments.1,2

Bronchial atresia is usually asymptomatic and discovered incidentally on a routine chest radiograph or CT.1,3 Most cases are noted in young adults, and there is a male predominance. Physical examination may reveal decreased breath sounds over the affected portion of the lung. Symptomatic patients can present with recurrent chest infection, dyspnea, wheezing, or chronic cough.

Classic findings on chest radiographs include a round or tubular opacity, corresponding to mucoid impaction of the bronchus, with adjacent hyperinflated-lung parenchyma, which has diminished vascular markings. The finding of associated overinflated lung helps establish the diagnosis. However, if the overinflation is not recognized, the lesion can be confused with arteriovenous malformation, granuloma, or a metastatic lesion.

CT is the study of choice for the diagnosis of bronchial atresia.3-6 It easily shows the tubular branching bronchus with mucoid impaction and the segmental hypoattenuated lung distal to the impacted bronchus. The absence of feeding arteries or draining veins helps to exclude a vascular lesion.

Since the majority of patients are asymptomatic, treatment is unnecessary. Surgical excision may be indicated in patients with recurrent infection or respiratory compromise.

Conclusion

A branching tubular structure with surrounding overinflated lung parenchyma is virtually diagnostic of congenital bronchial atresia. Low-dose CT with multiplanar or 3-dimensional reconstructions plays a very important role in establishing the diagnosis by showing the obstructed bronchus and adjacent lung with findings of overinflation.

References

- Kinsella D, Sissons G, Williams MP. The radiological imaging of bronchial atresia. Br J Radiol. 1992;65:681-685.

- Travis WD, Colby TV, Koss MN, et al. Congenital anomalies and pediatric disorders. In: King DW. (ed) Atlas of nontumor pathology: Non-neoplastic disorders of the lower respiratory tract. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology and the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. 2002;939.

- Gipson MG, Cummings KW, Hurth KM. Bronchial atresia. RadioGraphics. 2009; 29:1531-1535.

- Berrocal T, Madrid T, Novo C, et al. Congenital anomalies of the tracheobronchial tree, lung, and mediastinum: Embryology, radiology, and pathology. Radiographics. 2004;24:e17.

- Daltro P, Fricke B, Kuroki I, et al. CT of congenital lung lesions in pediatric patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;183:1497-506.

- Siegel MJ. Lung, pleural and chest wall. In: Siegel MJ. (ed) Pediatric Body CT, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008;69-120.