3D printed models of glenoid can aid shoulder arthroplasty

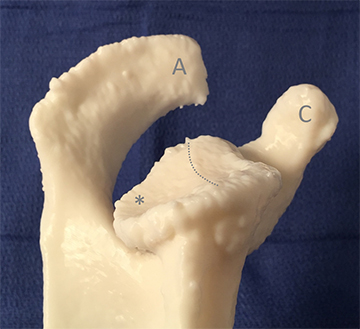

3D printed model demonstrating glenoid retroversion (note the

relative loss of bone posteriorly, marked with an asterisk)

and glenoid biconcavity(with the dotted line indicating a ridge

between the two glenoid facets). For orientation, the cromion

is marked "A" and the coracoid process is marked "C."

Computed tomography (CT) scans and humerus-subtracted volume rendering from thin-slice CT images are essential components of pre-surgical planning for shoulder arthroscopy. In complex cases, three-dimensional (3D) printed models can be even more beneficial, according to the Journal of Digital Imaging, in which a multi-institutional team of radiologists describe their experiences with shoulder surgeons.

Imaging is used to assess bony features of the glenoid. These include osteophyte formation, bone quality, bone stock assessment, posterior thinning, glenoid retroversion, glenoid biconcavity, and the glenoid central access. The true margins of the glenoid can be clarified with CT images, and the degree of subchondral bony sclerosis and cystic change at the glenoid may be demonstrated. The choice of surgical technique and the success of glenoid component fixation are determined in part from CT image analysis and volume rendering.

Hypothesizing that image-based 3D printed models could be more useful than 3D volumetric images in complex cases, principal investigator Kenneth C. Wang, MD, PhD, a staff radiologist at the Baltimore VA Medical Center, and co-authors created nine 3D models representing a spectrum of glenoid pathologies relevant to shoulder arthroplasty. These pathologies included osteophytes, glenoid bone loss, retroversion, and biconcavity. Dr. Wang said the goal was to select shoulders with bone loss and bone deformity that would exemplify some of the challenges that surgeons face in doing shoulder replacement surgery.

Working with four orthopedic shoulder surgeons, the retrospective study compared CT image review, including multiplanar reconstructed images, with humerus-subtracted volume-rendered images, and with inspection of 3D printed models. The surgeons were asked to score the clarity of the glenoid morphology on a 1-5 scale after reviewing the source CT images, then after reviewing the volume rendering, and finally after reviewing the printed model. The surgeons were also asked to rate the complexity of the glenoid the usefulness of the 3D model, both on a 1-5 scale.

The researchers then compared all the rankings. In all cases, the printed models outperformed the other categories. There was also a statistically significant positive correlation between the complexity of the morphology and the utility of the model.

“This did not surprise us,” Dr. Wang said. “Often there is a small amount of deformed bone at the ‘socket side” of the shoulder joint that may be difficult to fully appreciate on CT. Surgeons try to correct for this bone loss and bone deformity at the time of surgery in order to improve the functional outcome of the operation, and to promote the long-term durability of the hardware they place.”

The orthopedic surgeons said that the anatomic scale of the models could help to size devices and bone grafts, and would be useful in planning glenoid pin placement. They emphasized that “models would help in understanding the spatial orientation of the glenoid intraoperatively and that they more fully illustrate the true degree of retroversion and biconcavity.”

Dr. Wang noted that some models were more useful than others, and that the material selected to make the 3D printed model could also have an impact. “In one case, use of a translucent material enabled the surgeons to see through the bone to the edges of the ‘glenoid neck’. The center of this space is a key target of one of the primary steps in the operation,” he explained. “The translucent physical model let the surgeon see those landmarks in a way which isn’t possible when looking at the CT images or the volume rendering. It’s also not possible when the surgeon is looking at the exposed bone in the operating room. So with this material in particular, the printed model gives some unique advantages.”

Creating these 3D models is labor intensive. Dr. Wang said that each took several hours to segment and several hours to print. Radiologists are not being reimbursed for this yet.

“From the perspective of the radiology department, I would generally recommend a printed model when the bony pathology is severe enough that I think the images and volume rendering fail to adequately capture the structure of the bone,” said Dr. Wang. “My personal experience as a radiologist is that 3D printing has helped me to collaborate with physicians from other specialties, to learn more about the key clinical questions behind imaging requests, and to make imaging even more useful in the care of patients.”

REFERENCE

- Wang KC, Jones A, Kambhampan S, et al. CT-based 3D printing of the glenoid prior to shoulder arthroplasty: Bony morphology and model evaluation. J Digit Imaging. Published online February 28, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s10278-019-00177-4.