Thyroid nodules: When to biopsy

Images

Dr. Vandermeer is an Assistant Professor of Radiology, and Dr. Wong-You-Cheong is an Associate Professor of Diagnostic Radiology and the Director of Sonography, Department of Diagnostic Radiology, University of Maryland Medical Center, Baltimore, MD.

Thyroid nodules are extremely common. In a frequently cited postmortem series, nodules were found in 50% of the study population. 1 Thyroid nodules are more prevalent with increasing age, but the majority of these nodules are undetectable by physical examination. 2 Palpable nodules occur in 4% to 7% of the population; however, high-resolution ultrasonography (US) reveals nodules as small as 2 mm in 35% to 67% of the general population. 3-6 In addition, thyroid nodules are increasingly found incidentally on cross-sectional studies performed for nonthyroid indications. Fortunately, the vast majority of these nodules are benign (adenomas and adenomatoid nodules of multinodular goiters); approximately 2% to 12% are found to represent malignancy upon further work-up. 4,7 The diagnostic challenge is to efficiently and effectively diagnose the minority of patients with thyroid malignancy, while limiting the medical, emotional, and financial burden placed on the overwhelming excess of patients with benign nodules.

Ultrasonography of the thyroid gland has emerged as an important diagnostic tool in this process. Sonographic features of malignant and benign thyroid nodules have been established, but these have variable specificity and sensitivity. Nodules with highly suspicious features (to be discussed below) should undergo diagnostic fine-needle aspiration (FNA) prior to surgery. However, a clear distinction between potentially malignant nodules that require FNA biopsy and benign "leave alone" nodules is not always feasible because of considerable overlap in the US features of benign and malignant nodular thyroid disease. This article will review the epidemiology of thyroid cancer, the role of US in the triage of thyroid nodules for biopsy, and areas of continuing controversy where specific research studies may further clarify this complex subject in the future.

Clinical context of thyroid cancer

There are 4 main types of thyroid cancer: papillary, follicular, medullary, and anaplastic. Papillary carcinoma accounts for the majority, 80%, and follicular is the second most common type, comprising 10% to 20% of cases. Medullary and anaplastic subtypes are rare, with medullary carcinoma responsible for 3% to 5% and anaplastic for 1% to 2% of thyroid cancers. 8,9 Patients with papillary and follicular cancers tend to present with well-differentiated cancers that often do well after treatment, despite the presence of metastases to cervical lymph nodes in 20% to 50% of cases. 10 They are slow-growing and have a good prognosis with very low mortality and recurrence rates at 30 years. The 30-year survival rate for papillary cancer is approximately 95%. 11 In fact, autopsy reports have shown a high rate of clinically occult thyroid cancer with small, incidental, papillary tumors found in up to 13% of the U.S. population and 35% of the population in some European countries. 12,13

In contrast, the clinical diagnosis of thyroid cancer is relatively rare, constituting only 1% of new cancer diagnoses each year. 14 The discrepancy between occult thyroid cancer and clinically diagnosed disease supports the long-recognized existence of a subclinical form of thyroid cancer. 15 The incidence of clinical disease has rapidly increased over the past 3 decades from a rate of 3.6 per 100,000 in 1973 to 8.7 per 100,000 in 2002. 15 Interestingly, this increase is predominantly due to a dramatic increase in the diagnosis of small papillary cancers, and the mortality rate from thyroid cancer has been unaffected over the same period, remaining stable at approximately 0.5 deaths per 100,000. These findings suggest that the increasing incidence more likely reflects improved detection of subclinical disease as the use of thyroid US has become more widespread, rather than a rise in the true occurrence of the disease.

Ultrasound in the evaluation of palpable and incidentally found thyroid nodules

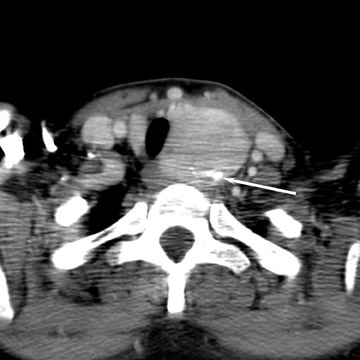

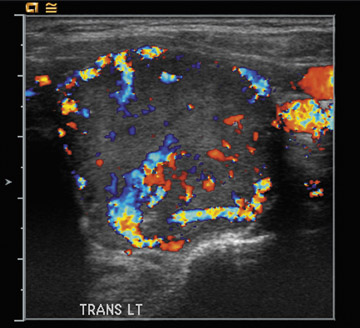

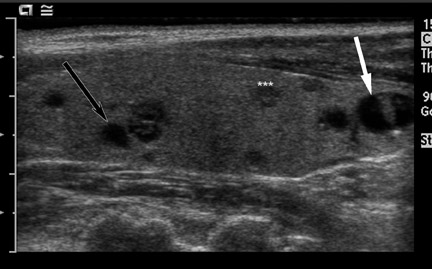

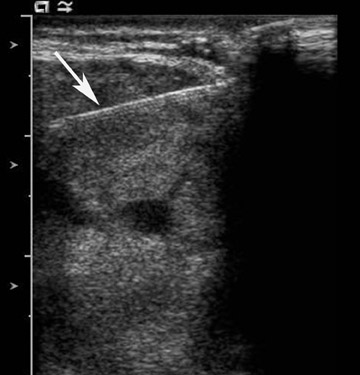

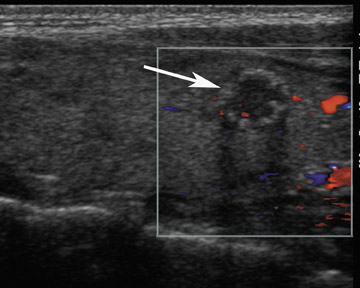

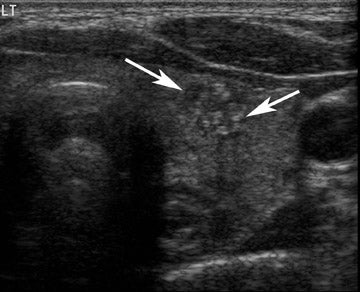

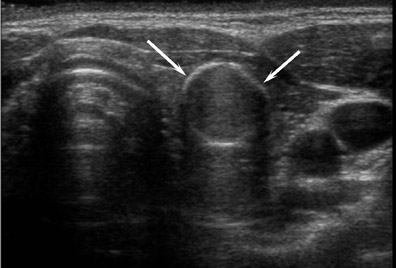

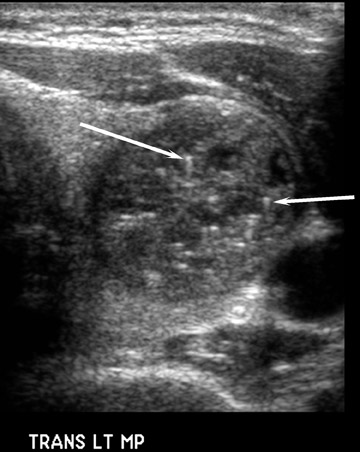

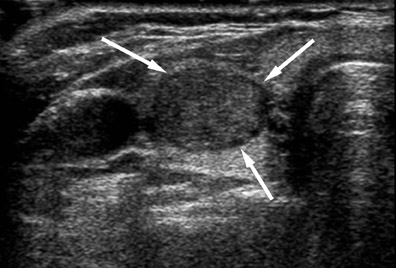

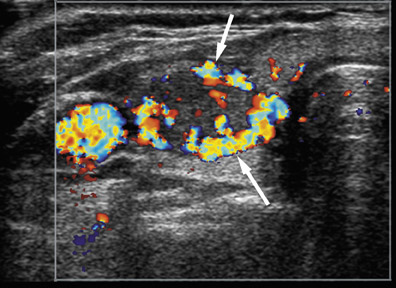

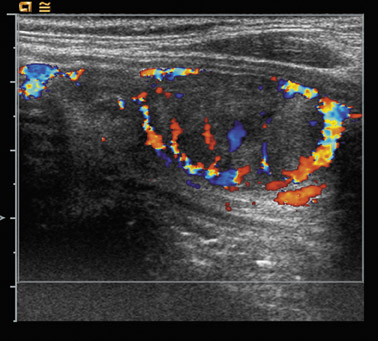

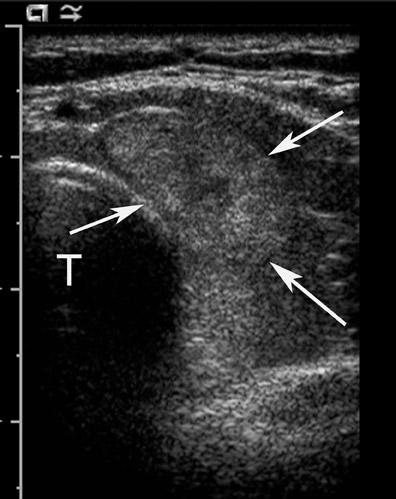

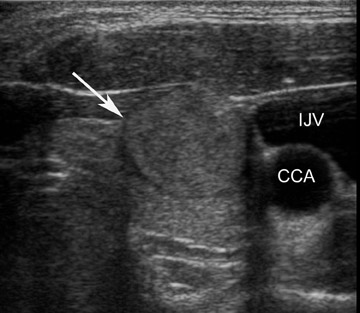

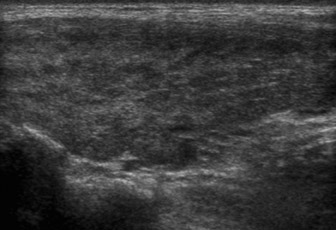

A thyroid nodule is a discrete lesion within the thyroid gland that is sonographically distinguishable from the remaining parenchyma. Thyroid nodules may present as a palpable finding on physical examination; however, they are increasingly being discovered as incidental findings on unrelated imaging studies, such as neck or chest computed tomography (CT), cervical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or carotid or parathyroid US (Figure 1). In most instances, patients with incidentally found thyroid nodules undergo US as the next step in their evaluation. Palpable nodules have traditionally been evaluated clinically by the determination of risk factors for thyroid cancer, such as neck irradiation and family history, followed by thyroid function tests. If the nodule is not hyperfunctioning, cytologic diagnosis is made by endocrinologist-performed FNA biopsy, usually without imaging guidance. However, as US has been shown to be more sensitive than physical examination, patients with palpable nodules are now more commonly also evaluated by US as a first step. 16,17 Ultrasound evaluation has the advantages of being able to characterize the presenting nodule, evaluate the rest of the thyroid for other nonpalpable nodules (often multiple) (Figure 2), and can be used to guide percutaneous biopsies (Figure 3). 18 As a consequence of the increasing use of diagnostic imaging-US in particular-we are in the midst of an epidemic of thyroid nodules.

The sonographic detection of thyroid nodules, and therefore thyroid cancer, at a smaller size and a presumed earlier stage raises the question of the clinical relevance of small thyroid cancers and any decrease in morbidity and mortality afforded to the patient. There have been no studies that have shown a clinical or therapeutic advantage to finding thyroid cancer at a smaller size. Are we truly helping patients when we diagnose small thyroid cancers that in many cases might have remained clinically occult? The answer to this question is difficult to determine because of the ethical considerations and impracticality of performing a study with nonoperative management of nodules with positive cytology.

Conversely, it is impractical to biopsy every incidentally found thyroid nodule and all of the additional nonpalpable nodules found by US in almost half of the patients with a palpable nodule. 18 In addition to the economic cost of thyroid US and FNA biopsies of these hundreds of millions of nodules, the diagnosis of thyroid cancer would increase dramatically, with additional economic costs and morbidity associated with surgery, its complications, and any potential adjuvant therapy. These issues highlight the need for a practical, cost-effective and safe approach for the management of thyroid nodules. Currently, US is the most effective imaging modality used for evaluating nodules prior to FNA or surgery.

Which nodules should be biopsied?

The overall incidence of malignancy in patients with thyroid nodules selected for FNA is between 9% and 13%, regardless of the number of nodules present and regardless of whether the nodule is a palpable or a nonpalpable incidental finding. 19 Ultrasound evaluation plays an important role in selecting which nodules need to be biopsied. Many studies have sought to define US features that may distinguish benign from malignant nodules. This, however, has proved to be an elusive goal. While there are definite US features that have been shown to be associated with thyroid malignancy, several of these features are variably seen, and others show a great deal of overlap with the US features of benign nodules. Selecting which nodules to biopsy involves incorporating an understanding of these US features, the classic patterns that are seen in specific conditions, and the general recommendations put forth by the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound addressing the issue of when to perform a biopsy. Additionally, the importance of clinical context should not be underestimated.

Sonographic features

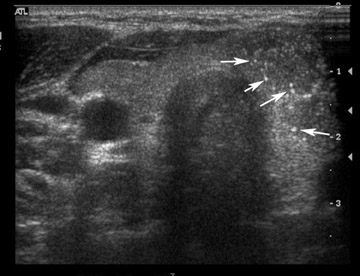

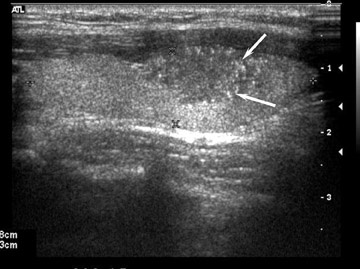

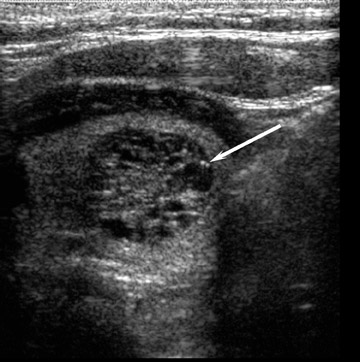

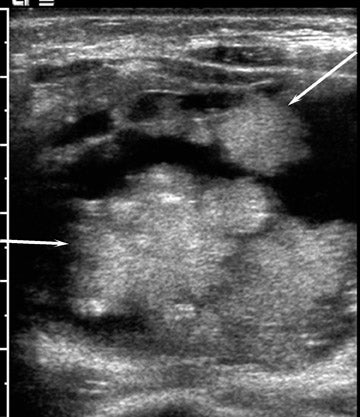

When present, fine, nonshadowing echogenic foci representing microcalcifications are highly indicative of papillary thyroid cancer, with a specificity of 95% (Figures 4 and 5). 20,21 However, this finding has a low sensitivity (29% to 59%), since microcalcification is often not present in malignant nodules. 21-24 Additionally, thyroid cancer may show a variety of other types of calcification, including irregular coarse calcification (Figure 6) and, rarely, peripheral "egg-shell" calcification (Figure 7)-calcification types that are more commonly seen in benign nodules (Figure 8). 20,24

Microcalcification must be distinguished from the inspissated colloid that may also appear as tiny echogenic foci. In contradistinction to microcalcification, the presence of colloid is a reliable indicator of benignity. 25 High-frequency US will demonstrate comet-tail or ring-down artifact (Figures 9 and 10) with colloid, which is not seen with microcalcification.

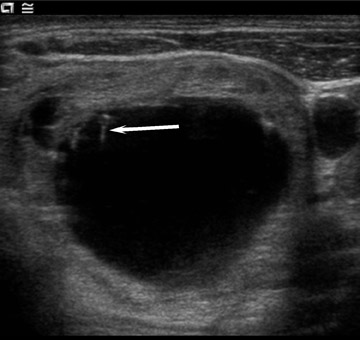

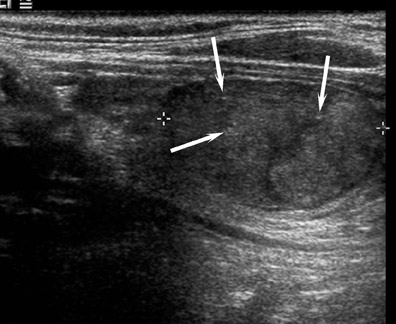

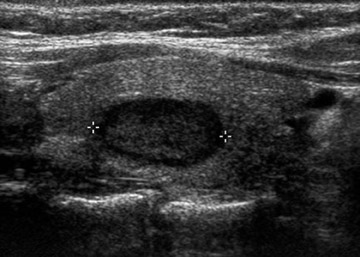

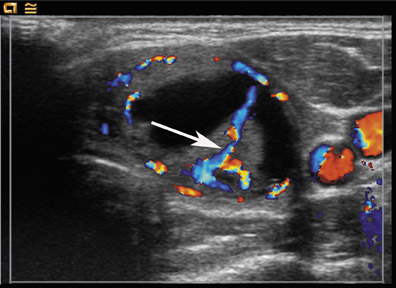

Several other US features have been evaluated for their ability to predict malignancy. A hypoechoic or anechoic rim encircling a nodule, known as the halo sign (Figure 11), suggests benignity; however, this sign may be absent in >50% of benign nodules and present in up to 20% of malignant nodules. 20 Marked hypoechogenicity, an irregular margin, a shape that is taller than wide, a solid composition, the absence of a halo, and intranodular vascularity (Figures 1, 6, and 12) have been identified as characteristics that are suggestive of malignancy. 21,22,26-29 Because of variable sensitivities and specificities, these criteria have limited diagnostic utility, and no one feature has been shown to have both a high sensitivity and a high predictive value for thyroid cancer. 19 Purely cystic lesions (Figure 9) without solid components or internal flow are generally considered to be benign, although they are not void of a malignancy risk. There is a 14% cancer risk, especially if the cyst recurs after aspiration. 30 It is important to note that nodule size and multiplicity have not been shown to affect the likelihood of malignancy. 21,22,29,31 While the rate of cancer per nodule decreases, this reduction is proportional to the number of nodules present, so the overall risk of malignancy per patient remains unchanged in patients with multiple nodules. 29,31

Classic patterns

An awareness of several classic patterns of specific benign and malignant entities should help to guide management decisions. Based on their extensive experience at the Mayo clinic, Reading et al 32 have proposed a pattern-oriented practical approach to the US evaluation of nodular thyroid disease, describing 8 typical appearances of commonly encountered benign and malignant nodules. This approach can triage >50% of thyroid nodules into observation or FNA categories and is not dependent on whether the nodule is palpable or single.

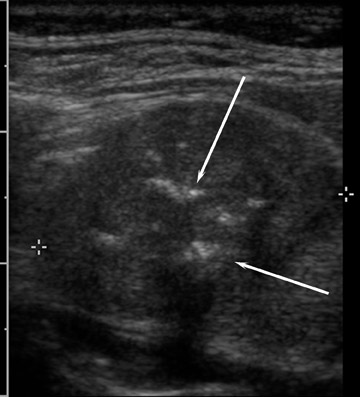

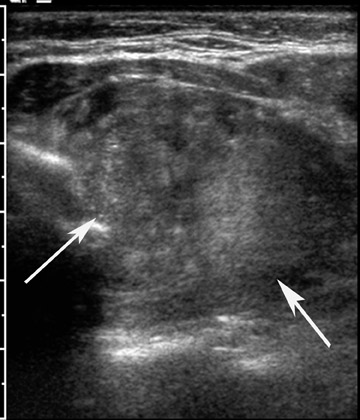

Four classic patterns have been described for nodules that need to be biopsied. The most specific pattern is a hypoechoic nodule with micro-calcifications, which has a positive predictive value of 70% for papillary carcinoma (Figures 4, 5, and 7). 22,33,34 Secondly, coarse calcifications in a hypoechoic nodule (Figures 6 and 13) also indicate the need for cytologic evaluation, as these nodules may represent either papillary or medullary carcinoma. While coarse calcification can be found in both benign and malignant nodules, a central location (Figures 6 and 13) is more suspicious and warrants FNA. Thirdly, well-marginated, ovoid, solid nodules with a thin hypoechoic halo (Figures 14 through 16) are likely to be follicular lesions and warrant FNA. These may have a central vascularity. Pathologically, these follicular lesions consist of follicular adenomas, carcinomas, and cellular adenomatoid nodules. As these cannot be reliably distinguished by cytologic evaluation, surgical excision is required to make the distinction between these entities. The fourth classic pattern is that of a solid mass with refractive shadowing from the edges, which is believed to occur as a result of fibrosis. Internal microcalcifications may be present.

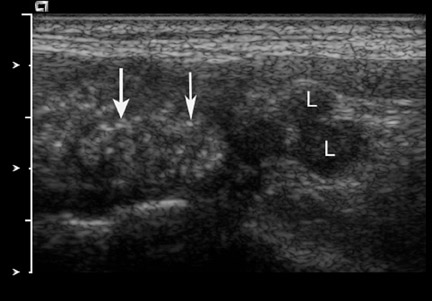

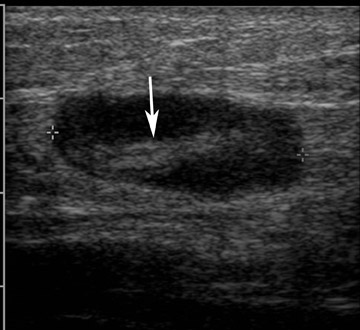

Equally helpful are the 4 classic patterns of nodules that do not require biopsy. Small (<1 cm) cystic nodules are benign colloid-filled cysts and are usually multiple (Figure 2). Internal echogenic foci with comet-tail artifacts represent colloid crystals. It is important to visualize the ring-down artifact with high-resolution transducers. A "honeycomb" appearance to a nodule that consists of internal cystic spaces with thin echogenic walls is indicative of a hyperplastic benign nodule (Figures 10 and 17). Foci of colloid with ring-down artifacts support this diagnosis. Thirdly, a large, predominantly cystic nodule is likely benign (Figure 9). However, one should pay close attention to the solid components to look for microcalcification, papillary excrescences, and a calcified nodule within a cyst (Figures 18 and 19). Mixed solid and cystic nodules are the most common finding in thyroid US and are often hyperplastic benign nodules with degeneration and internal debris as well as fibrosis (Figures 10, 17, and 20). Recent reports indicate that 40% to 53% of all benign nodules contained cystic components. 26,35 The relative amount of solid versus cystic components is often quoted in the literature, but this can be subjective. In general, the more solid a nodule, the more likely it is to be neoplastic and to need sampling. If a mixed solid and cystic nodule is selected for biopsy, aspiration should be targeted to the solid components or the areas with microcalcification. Finally, a pattern of diffuse, multiple small hypoechoic nodules with intervening echogenic bands (Figure 21) is indicative of Hashimoto's thyroiditis and does not require biopsy unless there is also a focal solid mass.

Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Statement

The Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound (SRU) convened a consensus conference in 2005 to sort through this complex topic in order to define general recommendations regarding how to manage thyroid nodules detected by US. A panel composed of radiologists, endocrinologists, surgeons, and cytopathologists reviewed the prevailing literature in order to define the characteristics that place one particular nodule at an increased risk for malignancy over another. Though nodule size does not correlate with risk of malignancy, a size cutoff was used in defining consensus recommendations in an attempt to balance the uncertainty of whether diagnosing small cancers conveys a mortality or morbidity advantage and to limit the potential for an excessive number of biopsies. 36 Based on these considerations, the recommendations apply to nodules >1 cm in size and are summarized in Table 1. 19 The recommendations are meant to provide the physician with general guidelines and some flexibility in the selection process, and are not meant to be absolute, inflexible criteria.

Lymph node assessment

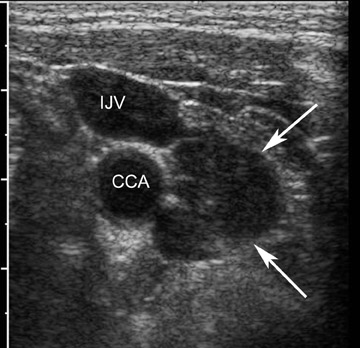

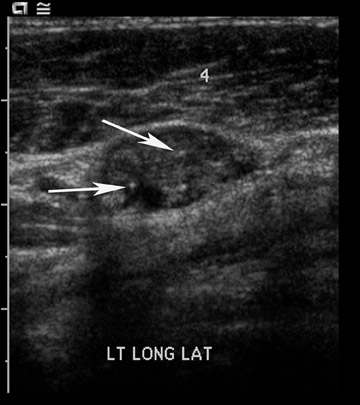

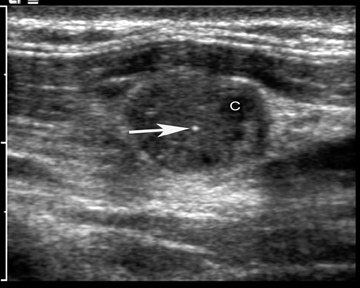

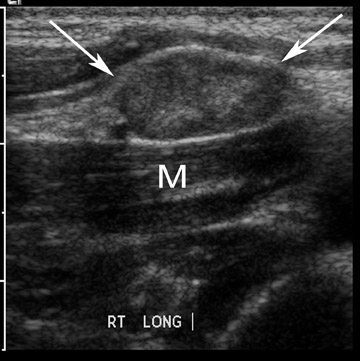

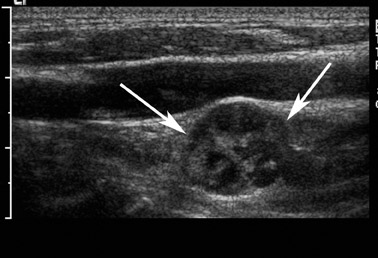

Evaluation of cervical lymphadenopathy is an integral component of the US evaluation of thyroid cancer. The finding of suspicious lymph nodes may override other US features and may prompt the biopsy of thyroid nodules. Some patients may present with enlarged lymph nodes secondary to occult thyroid cancer. Small cervical lymph nodes are not uncommon, and the diagnostic challenge is to distinguish reactive from malignant lymph nodes. Most metastatic nodes are found in the internal jugular chain. As in imaging evaluation of other malignancies, size matters. 37 Using a cutoff of 7 mm for short-axis diameter at level 2 and 6 mm at other levels, investigators reported 93% sensitivity, 83% specificity, and 88.5% accuracy in the US determination of metastasis from papillary thyroid carcinoma. 38 In addition to size, a round node is more suspicious than an elliptical node (Figures 22 and 23).

Microcalcifications are highly suggestive of metastatic papillary carcinoma (Figures 24 and 25) and can be found in approximately 50% of metastatic nodes. 38 Increased echogenicity of the node relative to adjacent muscle (Figure 26) and internal cystic change (Figure 27) are also suggestive and are found in 86% and 20% of metastatic nodes, respectively. 39,40 Microcalcification and cystic change are not seen in reactive lymph nodes and are, therefore, more specific features. Other helpful signs are irregularity of nodal margin and loss of echogenic fatty hilum. 41

Clinical considerations

It is important to consider clinical context in the decision-making process when selecting which nodules to biopsy. Specific factors, including patient history and findings on physical examination, may place a patient at an increased risk for thyroid cancer, and thereby lower the threshold for biopsy. Thyroid nodules in patients who are younger than 20 years and older than 70 years show a higher incidence of thyroid cancer, while the proportion of nodules that are malignant is double in males compared with females. 42 Patients with a history of neck irradiation, or a family or personal history of thyroid cancer, are also at an increased risk for malignant nodular thyroid disease. 43 Medullary thyroid cancer is associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia, type II. Physical examination findings that raise suspicion for malignant disease include a firm, hard, or fixed nodule, rapid growth, a nodule in the setting of dysphagia or hoarseness, and lymphadenopathy. 44 The decision of whether or not to biopsy a particular thyroid nodule should be based on the features of the nodule considered in light of the patient's individual clinical circumstances.

Areas for further investigation

The authors have attempted to define US criteria for the evaluation of thyroid nodules and also to convey the complexity of the clinical conundrum of how to manage thyroid nodules. This topic remains replete with questions for future research. What is the true clinical significance of small papillary carcinomas in terms of improved mortality or morbidity associated with early detection? How should clearly benign FNA results be followed? What constitutes substantial interval growth, especially in a nodule that has been shown to be benign by previous biopsy? In a patient with multiple nodules, which and how many nodules should be biopsied? Answers to these questions and the results of continued research in this area have great potential to further clarify the process of selecting thyroid nodules to be biopsied. Ideally, future guidelines, and perhaps new diagnostic tests, may help us diagnose the minority of patients with thyroid malignancy within the majority of benign masses.