Basilar artery transection after closed head trauma

Images

CASE SUMMARY

A 40-year-old male with unknown past medical history presented to the Emergency Department as a trauma after being struck by a vehicle at high speed. In the trauma bay, the patient was intubated with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 3. Relevant physical exam findings included hemotympanum with periorbial ecchymyosis and pupils that were dilated to 6mm and sluggish. Initial imaging showed subarachnoid blood and the patient was taken to the operating room for ventriculostomy placement. A significant amount of blood-colored CSF was discovered with an opening intracranial pressure of 75mmHg. Following the operation, the patient was transferred to neurointensive care, where he was pronounced brain dead and he ultimately expired. Autopsy was later performed.

IMAGING FINDINGS

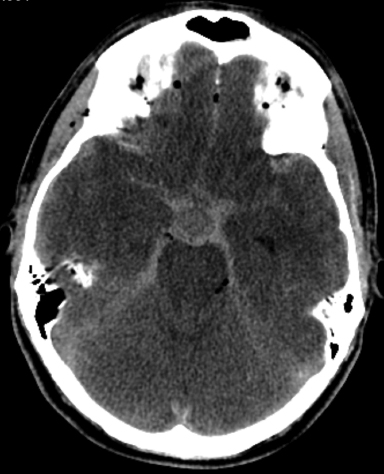

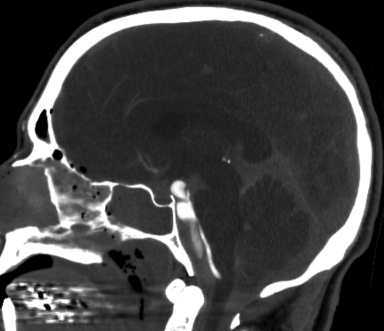

On initial physical exam, the patient demonstrated signs of skull base fracture, including periorbital ecchymyosis (Figure 1) and hemotympanum.1 The patient underwent a noncontrast head CT that showed a large amount of subarachnoid blood and extensive skull base fractures involving the anterior, middle, and posterior cranial fossas. There was also a hypoattenuating area adjacent to the basilar artery, which represented active extravasation of blood into the already present subarachnoid blood products (Figure 2). A CTA head was then performed, which demonstrated basilar artery transection with active contrast extravasation into the prepontine cistern (Figure 3). Finally, autopsy images of the brain confirmed the transected basilar artery (Figure 4).

DIAGNOSIS

Basilar artery transection and skull base fracture following closed head trauma

DISCUSSION

The unfortunate case described above demonstrates a unique radiology and pathology correlation of an extremely rare injury. Although the prevalence of blunt cerebrovascular injuries are difficult to measure, it is estimated to occur in about 1.2 percent of all blunt head trauma cases.2 Of those cases, the vast majority involve the internal carotid and vertebral arteries. A review of the literature focused on basilar artery pathology is very limited and only includes cases of basilar artery occlusion or aneurysm formation.3 An isolated basilar artery transection with skull base fracture after closed head trauma is a unique injury.

A review of the patient’s initial physical exam findings revealed three major findings worrisome for severe head trauma, and specifically skull base fracture. First, the patient had hemotympanum, which is a classic finding of skull base and temporal bone pathology.1 Second, the patient had periorbital ecchymyosis, or raccoon eyes, which also is an indication of skull base pathology.4 Finally, the patient was admitted with a GCS of 3, indicating that he had significant neurological deficits upon admission.

The patient’s initial noncontrast CT scan showed significant subarachnoid blood products with extensive skull base fractures. With the extent of subarachnoid blood, a large vessel injury was suspected. In addition to the subarachnoid blood and skull base fracture, there was also a hypoattenuating area adjacent to the basilar artery in the prepontine cistern compatible with hyperacture hemorrhage into the already present subarachnoid blood. This was a classic representation of the “swirl sign”5 in a rare location. The swirl sign is usually seen in the subdural space during acute hemorrhage into subacute or chronic blood products.

A CT angiogram was then performed for diagnostic confirmation of vessel injury. It showed active contrast extravasation from the basilar artery into the prepontine cistern. This was demonstrated with the “spot sign.”6

The severity of the patient’s injuries were not compatible with life and the patient ultimately expired approximately 6 hours after admission. At autopsy, a significant amount of subarachnoid blood was found upon initial examination of the brain. In addition to the blood, extensive skull base fractures involving the anterior, middle, and posterior cranial fossas were present. Finally, examination of the basilar artery showed complete transection.

CONCLUSION

Overall, the case described above details some of the classic physical exam and computed tomography findings associated with a skull base fracture and subarachnoid bleed with associated hyperacute hemorrhage after closed head injury. The classic findings in this case are associated with an extremely rare and unique pathology, a basilar artery transection. The basilar artery transection is extensively evaluated in our case with radiology and pathology correlation.

REFERENCES

- Watanabe K. Hemotympanum. The New England Journal of Medicine Images in Clinical Medicine. 2012;366:e14.

- Berne JD, Reuland KS, Villarreal DH, McGovern TM, Rowe SA, Norwood SH. Sixteen-slice multi-detector computed tomographic angiography improves the accuracy of screening for blunt cerebrovascular injury. Journal of Trauma. 2006;60(6):1204-1209.

- Shaw CM, Alvord E. Injury of the basilar artery associated with closed head trauma. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1972;35:247-257.

- Tarolli C, Scully MA, Smith III AD. Teaching neuroimages: Unmasking raccoon eyes. Neurology. 2014;83:e58-e59.

- Al-Nakshabandi, NA. The swirl sign. Radiology. 218(2):433.

- Wada R, Aviv RI, Fox AJ, et.al. CT angiography “spot sign” predicts hematoma expansion in acute intracereral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2007;38:1257-1262.

Citation

ZS R, J S, M B. Basilar artery transection after closed head trauma. Appl Radiol. 2017;(12):14-15.

December 7, 2017