Diffuse Left Breast Enlargement and Microcalcifications Secondary to PASH

Images

CASE SUMMARY

A 37-year-old female presented with a 6-year history of gradual, painless, asymmetric left breast enlargement. During a prior workup, she had multiple prior biopsies and excisions, which reportedly demonstrated fibrocystic change. Per the patient, her left breast had become asymmetric at her first pregnancy and had further increased in size with three subsequent pregnancies. No isolated breast lumps were palpable on physical exam.

IMAGING FINDINGS

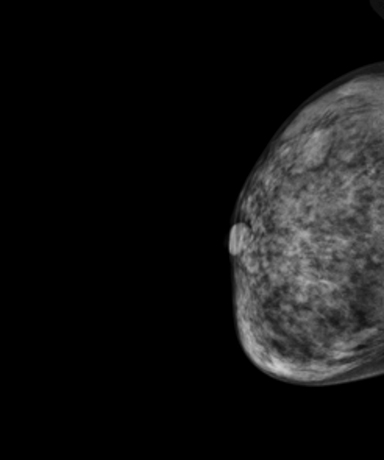

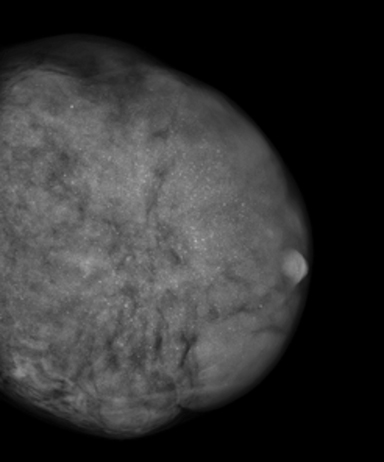

Mammography demonstrated asymmetric diffuse enlargement and increased density of the left breast with diffuse, round, and amorphous calcifications (Figure 1). The right breast, in comparison, demonstrated no abnormalities (Figure 1). An ultrasound of the left breast was obtained, revealing extensive heterogeneous breast parenchyma with both solid and fluid components and multiple associated punctate calcifications (Figure 2). Overall, the patient was given a BI-RADS 4 assessment, with tissue diagnosis recommended.

DIAGNOSIS

Post-excisional pathology revealed marked fibrocystic change, sclerosing adenosis with microcalcifications, pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH), and the absence of malignancy or atypia. The extent of PASH measured 15 cm. The patient did well postoperatively with excellent cosmetic results.

DISCUSSION

Microscopic PASH is a relatively common diagnosis on routine breast biopsy and excisional specimens. In fact, small foci of PASH have been reported in up to 23% of benign and malignant breast specimens.1 It is much rarer for PASH to be the primary pathological process of a breast lesion. Primary PASH usually presents as a focal asymmetry or mass by mammography, or clinically as a palpable lump. The 15cm lesion in our patient was far larger than the average size of PASH, reported to be 4-5 cm, with the range of diameters being 1 -11cm.1,2

On mammography, PASH appears most commonly as a noncalcified mass or localized region of increased stroma with a concordant well-defined, hypoechoic mass on ultrasound. The relatively nonaggressive appearance of the mammogram and ultrasound findings of PASH usually leads to an overall “probably benign” BI-RADS 3 assessment. An unusual finding in this case was the presence of diffuse, round, and amorphous calcifications on mammography, since PASH lesions typically lack calcifications.3 Although most calcifications associated with PASH can be accounted for by the histological presence of concomitant benign disease processes, a malignancy or a combination of malignancy and PASH should always be considered in such cases.3

A BI-RADS 4 assessment was assigned in this case due to the complexity of the findings and associated calcifications. The presence of calcifications in this particular case was likely due to concurrent sclerosing adenosis and fibrocystic changes; however, this highlights the fact that although PASH usually has benign features on imaging, rare cases of PASH have presented with radiological findings suspicious for malignancy.4 For example, Ferrira et al presented a case study of 26 patients with PASH, three of whom were suspicious for malignancy based on imaging findings of irregular margins or an ill-defined or spiculated nature of the lesion.5 Additionally, although PASH does not develop into carcinoma, the possibility of coexistent carcinoma in the vicinity of PASH does exist. There have been two relatively large studies demonstrating 10% and 4% of their total cases, respectively, as having coexistent carcinoma at the site of PASH.1,6

Although the pathogenesis of PASH remains uncertain, abnormal reactions to endogenous and exogenous hormones by fibroblasts are believed to play an important role. PASH has been associated with oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, and gynecomastia in men.7 Impressive decreases in the extent of PASH in patients taking Tamoxifen therapy have been reported, and similarities between PASH and the intralobular stoma in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle both lend support to the theory that hormonal stimulation plays a role in the etiology of PASH.2 In this case, rising hormone levels could explain the rapid breast enlargement that the patient experienced with each pregnancy.

Surgical excision is not necessary when lesions identified on core needle biopsy as PASH are associated with concordant imaging findings and malignancy has been excluded.8 Rates of lesion growth, as demonstrated by follow-up imaging, are variable and have been reported to be 0–71.4%.2, 9, 10 Excision of PASH generally can be considered in growing lesions as well as in BI-RADS 4 or 5 lesions, and when core needle biopsy pathology results are discordant with imaging findings.8 There have been variable reported rates of recurrence of PASH after excision, ranging from 0 to 28.5%, and rare reports of underlying malignancy highlights that PASH tumors require careful clinical and radiologic correlation and follow up.5, 9

CONCLUSION

PASH is typically encountered as an incidental microscopic finding after biopsy or as a noncalcified breast mass by mammography, but its presentation can vary. Breast imaging radiologists should therefore be aware of thediverse clinical and imaging findings to distinguish it from malignant processes.

REFERENCES

- Ibrahim RE, Sciotto CG, Weidner N. Pseudoangiomatous Stromal Hyperplasia: Some observations regarding its clinicopathologic spectrum. Cancer. 1989; 63:1154–1160.

- Vuitch MF, Rosen PP, Erlandson RA. Pseudoangiomatous hyperplasia of mammary stroma. Hum Pathol. 1986; 17:185–191.

- Celliers L, Wong DD, Bourke A. Pseudoangiomatous Stromal Hyperplasia: a study of the mammographic and sonographic features. Clinical Radiology. (1989; 65:145-149.

- Jones NK, Glazebrook KN, Reynolds C. Pseudoangiomatous Stromal Hyperplasia: imaging findings with pathologic and clinical correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010; 5:1036–1042.

- Ferreira M, Albarracin CT, Resetkova E. Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia tumor: a clinical, radiologic and pathologic study of 26 cases. 2008; Mod Path. 21:201-207.

- Hargaden GC, Yeh ED, Georgian-Smith D, Moore RH, Rafferty EA, Halpern EF, McKee GT. Analysis of the mammographic and sonographic features of pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008; 191:359-63.

- Powell CM, Cranor ML, Rosen PP. Pseudoangiomatous Stromal Hyperplasia: a mammary stromal tumor with myofibroblastic differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995 (19): 270-277.

- Gresik CM, Godellas C, Aranha GV, Rajan P, Shoup M. Pseudoangiomatous Stromal Hyperplasia of the breast: a contemporary approach to its clinical and radiologic features and ideal management. Surgery. 2010; 148:752-757.

- Polger MR, Denison CM, Lester S, Meyer JE. Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia: mammographic and sonographic appearances. Am J Roentgenol. 1996; 166: 349–352.

Citation

F S, K F, M B. Diffuse Left Breast Enlargement and Microcalcifications Secondary to PASH. Appl Radiol. 2020;(3):36-37.

May 5, 2020