Imaging transgender patients: Findings and complications

An estimated 1.6 million U.S. adults identify as transgender; this number is expected to grow as this demographic group gains societal acceptance.1 Yet, knowledge and awareness of the unique imaging considerations relating to these individuals are limited among radiology educators, according to a 2018 survey of 325 such professionals.2

Radiologists and other physicians representing 12 hospitals in Canada, France, and the United States provide guidance in an illustrated overview published in the August 2019 issue of Abdominal Radiology.

Imaging following male-to-female gender reassignment

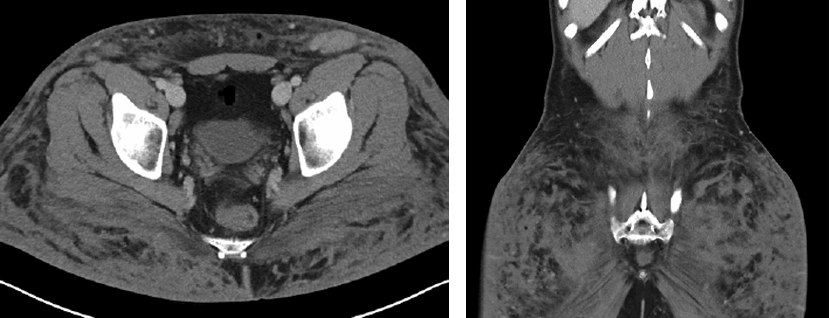

A 30-year-old female-to-male trangender patient presented with

right lower quadrant pain after recent silicone buttock injections.

Axial and coronal images show severe infiltration of the subcutaneous

tissues of the buttocks, consistent with recent silicone injections.

Image courtesy of Olga R. Brook, MD.

Genital reconstruction surgery includes removal of male organs, followed by vaginoplasty, labiaplasty, and clitoroplasty. Stenosis of the neovagina and urethral meatus are the most common complications of these surgical procedures. Complications from insufficient resection of erectile tissue can result in protrusion of the uretha. There can also be injury to the rectum and bladder, and perforation of the rectovaginal wall or development of a rectovaginal fistula. Bleeding, inflammation, ischemia, and infections may also occur.

Olga R. Brook, MD, an abdominal imaging radiologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, and co-authors state that the high-contrast resolution of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is excellent for evaluating postsurgical complications and anatomy. They explain that the orientation of the neovagina can be well assessed with MRI.

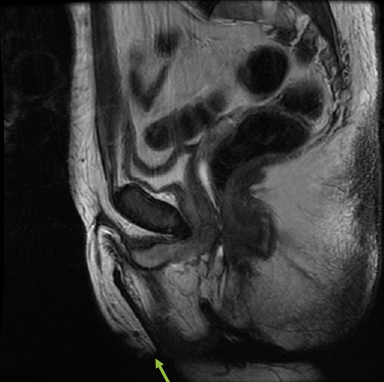

A 39-year-old female-to-male patient

after falloplasty and vaginectomy.

Sagittal images demonstrate normal

post falloplasty appearance with

trace of fluid in vaginectomy bed.

Image courtesy of Olga R. Brook, MD.

Suspected leaks and/or strictures can be identified with computed tomography (CT) or fluoroscopic neovaginograms, which can show mucosal folds when the bowel is used to create a neovagina. The authors also describe anatomical details that a radiologist can expect to see.

The authors suggest that transgender women have annual mammography screenings after age 50 if they have used, or are currently using, hormones such as estrogen and spironolactone, even though breast cancer development is rare in this group. Transgender women may be at risk for developing prostate cancer. The authors caution that radiologists who are unaware of a transgender patient’s clinical history may potentially misdiagnose the prostate as a pelvic mass, abscess, or fluid collection.

Imaging following female-to-male gender reassignment

Besides having a bilateral mastectomy with chest contouring, patients can undergo genital reconstruction, which includes creation of a neophallus, either with metoidioplasty or phalloplasty, urethroplasty, and scrotoplasty with testicular prostheses.

These surgeries are more prone to complications related to urethroplasty, such as urinary dribbling, urethral fistulae, and strictures, the authors write, adding that urethrocutaneous and urethrovaginal fistulae are the most common complications.

CT and MR imaging are recommended for post-surgical complications, with contrast-enhanced MRI to help assess vascular supply to the neophallus, and CT to assess testicular prostheses. The authors explain that fluoroscopic retrograde or voiding cystourethrogram is performed to assess augmented urethra, and pelvic ultrasound to evaluate abnormal uterine bleeding.

Complications such as silicone granuloma formation, pyomyositis, and/or deep venous thrombosis may result from non-surgical cosmetic procedures and hormone therapy. Patients who have mammoplasty should undergo screening mammograms.

Additionally, radiologists must be alert to what may appear as a pelvic mass on CT or MRI in patients who do not identify as transgender but whose prostate and seminal vesicles cannot be visualized. Such patients may not have undergone hysterectomy or oophrectomy.

“With increasing awareness of gender dysphoria and number of patients undergoing gender reassignment surgeries, it is crucial for radiologists to be aware of common surgeries, their associated complications, and their imaging appearances,” concluded the authors.

REFERENCES

- Shergill AK, Camacho A, Horowitz JM, et al. Imaging of transgender patients: expected findings and complications of gender reassignment therapy. Abdom Radiol. 2019;44(8):2886-2898.

- Clark KR, Vealé. Assessing transgender-related content in radiography programs in the United States: A survey of educators. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2018;49(4):414-419.