Novel MRI Approach Identifies Early Brain Cell Damage in Alzheimer’s Before Tissue Shrinkage

Research from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis shows that a mathematical analysis of data obtained with a novel MRI approach can identify brain cell damage in people at early stages of Alzheimer’s, before tissue shrinkage is visible on traditional MRI scans and before cognitive symptoms arise.

Research from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis shows that a mathematical analysis of data obtained with a novel MRI approach can identify brain cell damage in people at early stages of Alzheimer’s, before tissue shrinkage is visible on traditional MRI scans and before cognitive symptoms arise.

Alzheimer’s disease usually is diagnosed based on symptoms. MRI brain scans haven’t proven useful for early diagnosis in clinical practice. Such scans can reveal signs of brain shrinkage due to Alzheimer’s, but the signs only become unmistakable late in the course of the disease, long after the brain is significantly damaged and most people have been diagnosed via other means.

“This could be a new way to use MRI to diagnose people with Alzheimer’s before they develop symptoms,” said senior author Dmitriy Yablonskiy, PhD, a professor of radiology at the university’s Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology. “The technique takes only six minutes to acquire data and can be implemented on MRI scanners that are already used worldwide for patient diagnostics and clinical trials.”

Published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, the study relies on a new quantitative Gradient Echo (qGRE) MRI technique developed in the Yablonskiy lab to show brain areas that are no longer functioning due to a loss of healthy neurons.

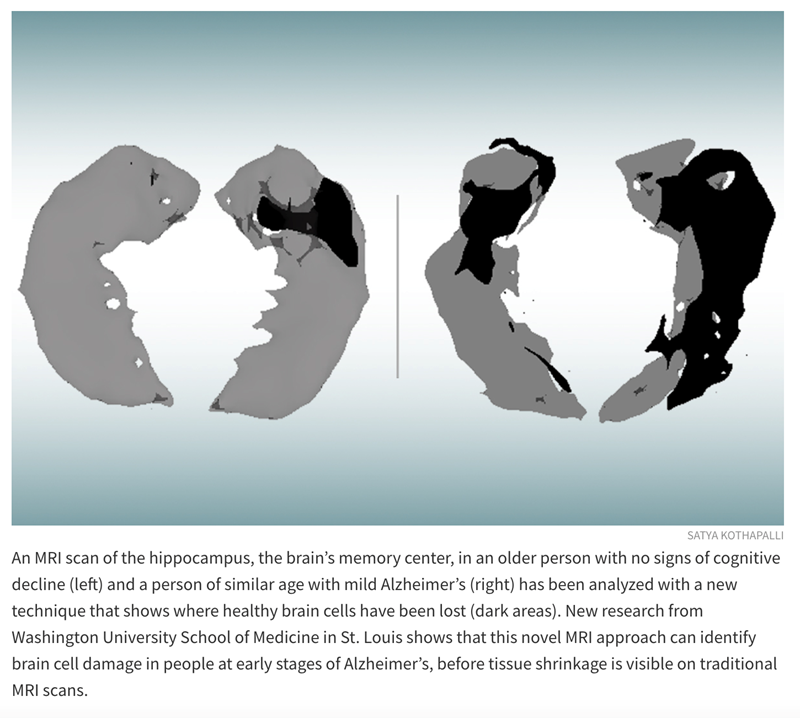

“Using this technique in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, we discovered brain areas that look normal on traditional MRI but look dark on qGRE images, which we attribute to significant neurodegeneration,” said Satya V. V. N. Kothapalli, PhD, a staff scientist in radiology and the first author of the study. “We call them ‘dark matter.’”

While traditional MRI is capable of showing where damaged areas of the brain have decreased in volume, the qGRE technique goes a step further, detecting the loss of neurons that precedes brain shrinkage and cognitive decline.

Alzheimer’s disease develops slowly over the course of two decades or more before symptoms arise. First the brain protein amyloid beta accumulates into plaques in the brain, then another brain protein — tau— coalesces into tangles and neurons begin to die. Finally, tissue atrophy becomes visible on MRI brain scans, and cognitive symptoms arise. People at early stages of the disease can be identified via amyloid-PET brain scans or by testing for amyloid in the blood or the cerebrospinal fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord, but such tests do not provide information on neuronal damage.

The study involved 70 people ages 60 to 90 who were recruited through the Charles F. and Joanne Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center (Knight ADRC). Participants completed extensive clinical and cognitive testing to assess their level of cognitive impairment. The participant group included people with no cognitive impairment as well as those with very mild, mild or moderate impairments.

Each participant underwent either a PET brain scan or a spinal tap to gauge the amount of amyloid plaques in his or her brain. They also underwent MRI brain scans.

Related Articles

Citation

Novel MRI Approach Identifies Early Brain Cell Damage in Alzheimer’s Before Tissue Shrinkage. Appl Radiol.

March 3, 2022