Parry-Romberg syndrome

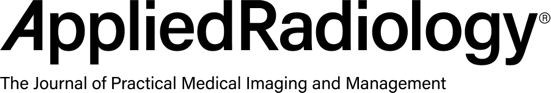

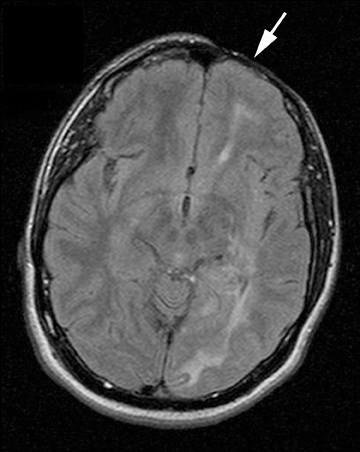

Transaxial FLAIR MR images (Figures 1A and 1B) demonstrate atrophy of skin and subcutaneous tissues overlying the left frontal calvarium (arrows), as well as ipsilateral cerebral atrophy and diffuse white matter hyperintensities involving the left frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes, external capsule, and corpus callosum splenium. Axial T2*-weighted, gradient-echo MR images (Figures 1C and 1D) demonstrate ipsilateral microhemorrhages involving the left isthmus of the cingulate gyrus, parietal and occipital white matter, thalamus, and corpus callosum splenium. Additionally, a cystic lesion lined by hemosiderin is demonstrated in the left superior frontal lobe (Figure 1E, arrowhead), consistent with old, encapsulated hematoma.

Discussion

Parry-Romberg syndrome, also known as progressive facial hemiatrophy, was first described by Parry in 1825 and Romberg in 1846. It is a rare disorder of unknown etiology characterized by unilateral wasting of the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the face with variable involvement of underlying facial muscle, cartilage, and bone. 15 percent of patients have neurologic manifestations that include epilepsy, migraine headache, cranial nerve deficits, hemiplegia, cognitive abnormalities, and fixed focal neurologic deficits.1,2 Cranial CT and MRI findings in Parry-Romberg syndrome are usually ipsilateral to the facial hemiatrophy, and include intraparenchymal calcifications, focal or diffuse white matter hyperintensities, focal infarction of the corpus callosum, loss of cortical gyration, cerebral hemiatrophy, and leptomeningeal enhancement.1-4 Reported neurovascular findings include multiple intracranial aneurysms, reversible vascular narrowing, and vascular malformation.5-7 Neurologic symptoms or signs may not be associated with detectable brain lesions, or they may precede the appearance of lesions. Moreover, the correlation between the severity of brain lesions and the clinical picture is unclear, since some patients with visible brain lesions on imaging are neurologically asymptomatic.

Although the etiology of Parry-Romberg syndrome is unknown, several causes have been proposed. It has been postulated that it actually falls within the spectrum of localized, linear scleroderma. Linear scleroderma, or “en coup de sabre,” refers to focal scleroderma of the face or scalp, resulting in characteristic facies resembling a face struck on one side with a sabre sword. Parry-Romberg syndrome has similar characteristics, but there tends to be more extensive involvement of the ipsilateral subcutaneous

tissue, calvarium, and orbit,3 and facial hemiatrophy is typical rather than the hemifacial cutaneous sclerosis that typifies linear scleroderma.8 In light of the similarity to linear scleroderma, some authors postulate chronic, progressive autoimmune neurovasculitis as the cause of Parry-Romberg syndrome.3,8-11 Other putative causes of this unusual disease include neural tube malformation, traumatic injury, vascular malformation, viral or bacterial infection, and hyperactivity of the sympathetic nervous system.3

In this case, cerebral microhemorrhages (CMH) are a prominent neuroradiologic manifestation. These microhemorrhages are visible as scattered, punctate (<5 mm), hypointense foci on T2*-weighted, gradient-echo MR imaging, are confined to the hemisphere ipsilateral to the facial atrophy, and are associated regionally with confluent white matter hyperintensities. In addition, there was a clinically silent, chronic “cystic” macrohemorrhage in the ipsilateral posterior frontal lobe on MR imaging. These findings shed some light on the pathogenesis of Parry-Romberg syndrome and suggest that in some cases, it may be due to a vasculopathy or vasculitis of small vessels. The neuropathology of the two most common diseases associated with cerebral microhemorrhages on MR imaging, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, and chronic systemic hypertension, are typified by a progressive small-vessel vasculopathy. With cerebral amyloid angiopathy, there is progressive amyloid deposition restricted to small- to medium-sized vessels of the brain that leads to fibrinoid necrosis and vascular frailty, and there is often associated diffuse multifocal white matter disease, and symptomatic lobar hemorrhage. The other common cause of cerebral microhemorrhages is chronic systemic hypertension, which leads to intimal hyperplasia and hyalinosis in deep, penetrating arterioles.12 The vasculopathic nosology suggested by the presence of cerebral microhemorrhages in this case would certainly be concordant with previous efforts to classify Parry-Romberg syndrome as part of the scleroderma spectrum since scleroderma is a connective tissue disease associated with systemic vasculitis.3,8-11 The findings in this case, therefore, suggest that some cases of Parry-Romberg syndrome may be secondary to a neurovasculopathy of small vessels that manifests as cerebral microhemorrhages.

Conclusion

Parry-Romberg syndrome, or progressive facial hemiatrophy, is a rare disorder of unknown etiology characterized by unilateral wasting of facial skin and subcutaneous tissue with variable involvement of underlying muscle, cartilage, and bone, as well as a variety of possible concomitant neurological abnormalities. Parry-Romberg syndrome has been proposed to be an overlapping condition with linear scleroderma, “en coup de sabre.” In the case reported here, the finding of unilateral cerebral microhemorrhages ipsilateral to facial hemiatrophy suggests that some cases of Parry-Romberg syndrome may be secondary to a small-vessel neurovasculopathy.

- Buonaccorsi S, Leonardi A, Covelli E, et al. Parry-Romberg syndrome. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:1132-1135.

- Aynaci FM, Sen Y, Erdol H, et al. Parry-Romberg syndrome associated with Adie’s pupil and radiologic findings. Pediatr Neurol. 2001;25:416-418.

- Grosso S, Fioravanti A, Biasi G, et al. Linear scleroderma associated with progressive brain atrophy. Brain Dev. 2003;25:57-61.

- Lederman RJ. Progressive facial and cerebral hemiatrophy. Cleve Clin Q. 1984;51:545-548.

- Pichiecchio A, Uggetti C, Eggito MG, Zappoli F. Parry Romberg syndrome with migraine and intracranial aneurysm. Neurology. 2002;59:606-608.

- Woolfenden A, Tong DC, Norbash AM, et al. Progressive facial hemiatrophy: abnormality of intracranial vasculature. Neurology. 1998;50:1915-1917.

- Miedziak AI, Stefanyszyn M, Flanagan J, et al. Parry-Romberg syndrome associated with intracranial vascular malformations. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:1235-1237.

- Orozco-Covarrubias L, Guzman-Meza A, Sanz-Ridaura C, et al. Scleroderma ‘en coup de sabre’ and progressive facial hemiatrophy. Is it possible to differentiate them? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:361-366.

- Terstegge K, Kunath B, Felber S, et al. MR of brain involvement in progressive facial hemiatrophy (Romberg disease): reconsideration of a syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:145-150.

- Stone J, Franks AJ, Guthrie JA, et al. Scleroderma ‘en coup de sabre’: pathological evidence of intracerebral inflammation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:382-385.

- Gambichler T, Kreuter A, Hoffmann K, et al. Bilateral linear scleroderma ‘en coup de sabre’ associated with facial atrophy and neurological complications. BMC Dermatol. 2001;1:9.

- Viswanathan A, Chabriat H. Cerebral microhemorrhage. Stroke. 2006;37:550-555.