Pediatric gastrointestinal emergencies

Gastrointestinal (GI) complaints are among the most frequent causes for emergency department visits in the pediatric population. Radiology plays an ever-increasing role in the diagnosis and treatment of these emergencies. This article describes the clinical presentation, epidemiology, and imaging findings of 5 GI emergencies that require surgical intervention: Malrotation and midgut volvulus; intussusception; hypertrophic pyloric stenosis; appendicitis; and Meckel's diverticulum.

Malrotation and midgut volvulus

Malrotation is any deviation from the normal 270º counterclockwise rotation of the bowel that occurs during embryogenesis. The resultant shortened mesenteric pedicle predisposes to midgut volvulus, a clockwise rotation around the superior mesenteric artery axis that can lead to bowel ischemia. A mnemonic for remembering the direction of rotation of volvulus and surgical devolvulus is: "the surgeon turns back the hands of time."

The incidence of malrotation is 1 in 500. 1 The male-to-female ratio is 2:1. Malrotation with midgut volvulus may become rapidly life-threatening. The previously healthy infant with bilious emesis is one of the few "drop everything else" presentations in pediatric imaging, as the stopwatch of ischemic bowel may be ticking. The older the child, however, the more atypical the symptoms; the teenager with chronic abdominal pain or malabsorption may be suffering from recurrent bouts of volvulus and devolvulus.

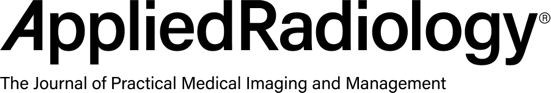

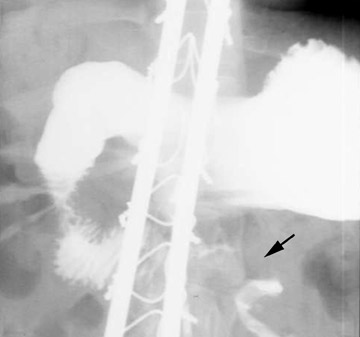

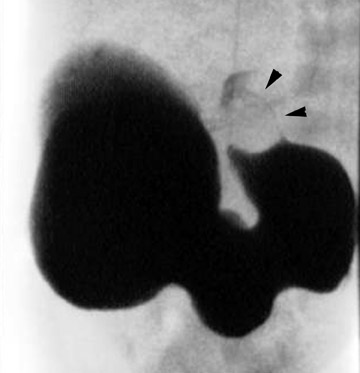

Conventional radiographs are neither sensitive nor specific for malrotation. On the upper GI series, it is crucial to locate the position of the duodenal-jejunal junction (DJJ). The DJJ must be at least over (but more reassuringly lateral to) the left vertebral pedicle and at the same height as the duodenal bulb on a well-centered view. If the DJJ does not meet these two criteria, then malrotation is diagnosed (Figure 1). Signs of midgut volvulus include an abrupt termination, or beak, of the contrast column (Figure 2) and the corkscrew (apple peel, or barber pole 2 ) sign (Figure 3).

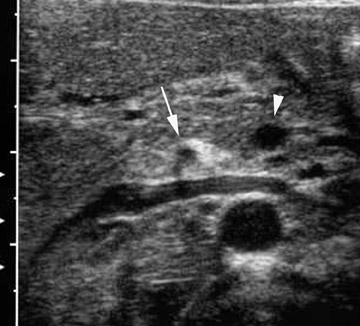

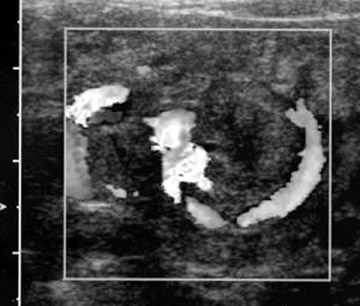

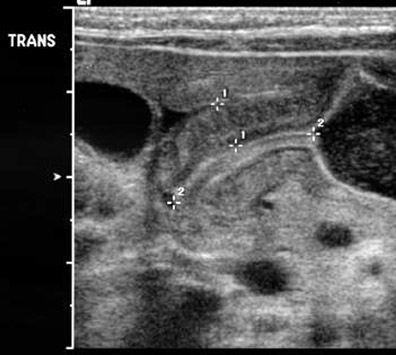

On ultrasound (US) and computed tomography (CT), the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and superior mesenteric vein (SMV) relationship may be reversed (Figure 4). Normally the SMV is to the right of the SMA; with malrotation, the SMV may occupy a position directly anterior or to the left of the SMA. Of critical importance, a normal SMA/SMV relationship does not exclude malrotation, and the upper GI remains the imaging gold standard. Conversely, some children without malrotation may have a vertical or inverted SMA/SMV relationship. 3 Several other US signs of midgut volvulus include: Hyperdynamic pulsating SMA 4 ; distal SMV dilation 5 ; whirlpool sign 6 (Figure 5); and a truncated SMA sign 7 (Figure 6). Two technical points should be kept in mind when evaluating the SMA/SMV relationship. First, scan as caudally as possible; at the portal confiuence, the SMV occupies the most ventrally vertical position with respect to the SMA and may erroneously suggest malrotation. Second, place the transducer over the midline and not over the liver; rightward deviation will falsely "move" the SMV to the left and possibly ventral to or left of the SMA. 8

Intussusception

Intussusception is the telescoping of a segment of bowel into an adjacent segment; the great majority of cases are ileocolic. In only 5% of cases is a pathologic lead point identified. 9 Lymphoid hyperplasia is the cause in the vast majority of the remaining 95%. The classic clinical triad is abdominal pain, currant-jelly stool, and palpable abdominal mass. However, in our experience, lethargy and drawing up of the legs are the most commonly reported signs, and a significant percentage of patients may be pain-free at presentation. 10 Most patients are between the ages of 6 months and 2 years.

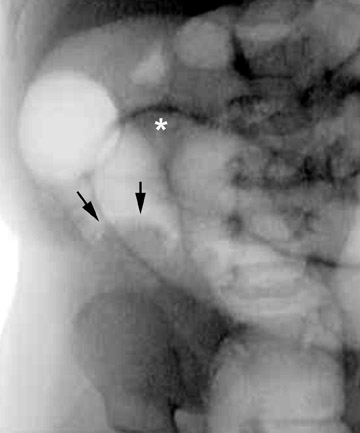

Conventional radiographs are neither specific nor sensitive. 11,12 Findings include the meniscus (Figure 7) and target signs. The most important use for radiographs is excluding pneumoperitoneum. A gas-filled cecum on a left lateral decubitus film is a good negative predictor for intussusception. However, determination of cecal position can be difficult; in 45% of children ≤5 years of age, a gas-/stool-filled sigmoid colon is positioned in the right lower quadrant and may mimic a normal-appearing cecum. 13 One less well-known sign that the authors have found to be predictive of intussusception is "ileization" of the right lower quadrant, ie, visualization of gas-filled small-bowel loops in the right lower quadrant, filling the "vacuum" left by the intussuscepted cecum and ascending colon (Figure 7).

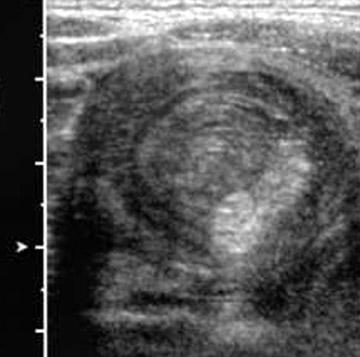

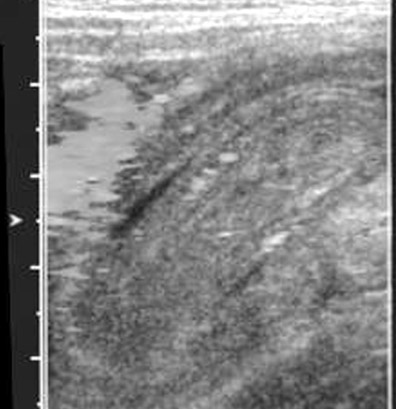

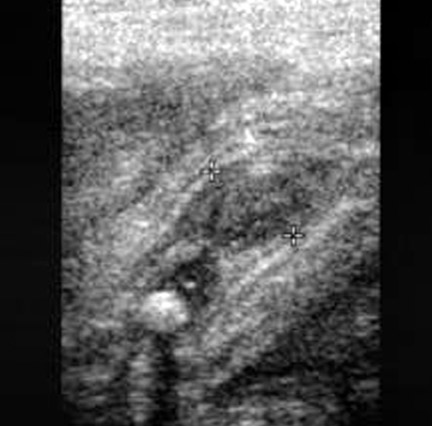

Several studies have reported 100% diagnostic accuracy rate for US, and US may be used to guide hydrostatic and air reduction. 14-17 A clear advantage is the lack of ionizing radiation. The technique is more widely used in Europe and Asia, but is gradually being adopted in the United States. Several US signs have been described: Doughnut; pseudokidney; crescent in doughnut (Figure 8A); sandwich (Figure 8B); and hayfork 16,18,19

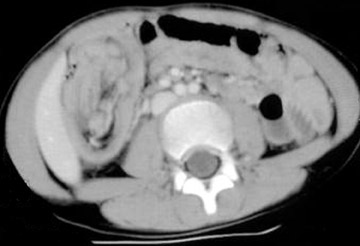

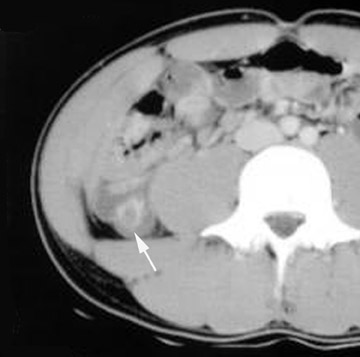

CT findings for intussusception are characteristic. The telescoping nature of the pathology is seen on axial images as an eccentric fat and soft-tissue density mass surrounded by bowel wall (Figure 9). The typically crescentic fat represents the mesentery drawn into the intussuscipiens, and the soft tissue is a combination of bowel, lymph nodes, and mesenteric vasculature.

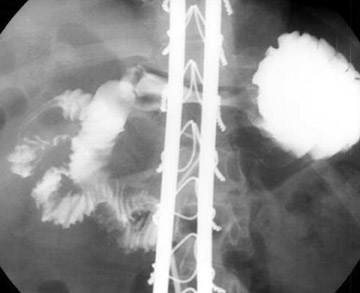

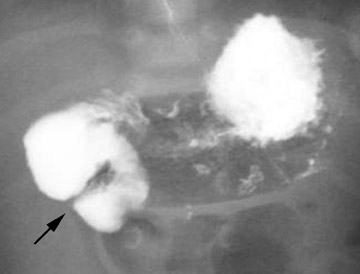

In most institutions, a contrast enema remains the standard for diagnosis and initial treatment. Peritonitis and perforation are absolute contraindications. The major complication is perforation with potential tension pneumoperitoneum. Prior to performing the enema, a surgical consult is required, the patient must have an intravenous (IV) line in place (for emergency resuscitation), and a large-bore needle (eg, 14-g catheter needle) should be within close reach to decompress a tension pneumoperitoneum. If the patient cries during the procedure, it is expected and beneficial; crying simulates the Valsalva maneuver and protects against bowel perforation by reducing the transmural gradient. 20 Explaining this to the parents both reassures and defiects requests for sedation. Whether air or liquid is used to perform the enema is a matter of personal preference. The rates of reduction of intussusception are not statistically different when using air versus liquid contrast 21 ; however, air is faster, uses less radiation, causes significantly smaller perforations, and results in less peritoneal contamination if perforation does occur. 20 Those who favor liquid point to the slightly lower perforation rate in large studies, superior visualization of pathologic lead points, and greater control over the lead pressure. 22

The authors favor the air enema for speed, decreased radiation dose, and cleanliness, reserving the contrast enema for children with a higher pretest probably of a pathologic lead point based on age (<1 month old or >4 years old). A negative study goes quickly, with rapid filling of the colon and refiux into the terminal ileum. In a positive study, the intussusceptum is usually encountered in the transverse colon, and the initial reduction proceeds rapidly to the ileocecal valve (Figures 10A and 10B). Disappearance of the cecal mass and free refiux of air into the terminal ileum indicates successful reduction (Figure 10C). How long to persist is controversial, with some advocating 3 attempts, a maximum pressure of 120 mm Hg, and limiting the duration of maximal pressure to <3 minutes. 23 Others will try longer, reasoning that both perforation and incomplete reduction will result in surgery. We have had excellent success with delayed attempts after initial incomplete reduction; after waiting 15 to 20 minutes (to allow the edematous bowel and ileocecal valve to decrease in size), a subsequent reduction attempt may be successful. 24 If tension pneumoperitoneum occurs, insert a large-bore needle (eg, 14-g catheter needle) in the midline abdomen through the avascular linea alba, 2 cm above the umbilicus.

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis

Several hypotheses have been proposed for hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS), including those focused on the pyloric muscle and its innervation, hormones, and a molecular etiology. 25,26 The typical patient is a male infant with a previously normal feeding history who presents with nonbilious, projectile emesis. In the premature infant, the diagnosis may be made at an older age. 27 Palpation may reveal an "olive" in the right upper quadrant; however, in 15% of cases, even highly experienced pediatricians and surgeons cannot make this diagnosis on physical examination. 28 The incidence of HPS is 1 to 4 cases per 1000 live births, with a 2:1 to 5:1 male/female ratio. 29 Patients usually present between the ages of 2 and 8 weeks, with peak incidence at 3 to 5 weeks. 30 With delayed diagnosis, the infant shows signs of dehydration, lethargy, and a hypochloremic alkalosis due to loss of stomach acid.

Ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice because it enables direct visualization of the pyloric muscle and avoids ionizing radiation. The pylorus is a hypoechoic structure with echogenic mucosa/ submucosa and serosa on either side (Figure 11). Although a narrow range of diagnostic measurement criteria have been published, the authors use the mnemonic π (3.14) to remember 3-mm thickness and 14-mm channel length. Practically, the appearance of HPS is characteristic, independent of measurements. A high-frequency linear transducer should be used. Allowing the infant to bottle-feed with glucose solution (NOT echogenic formula) will provide an acoustic window through the antrum and facilitate evaluation for liquid shuttling across the pylorus. A right posterior oblique position may displace air into the fundus and liquid against the pylorus, which will now lie in a more dependent position. An important component of the complete US evaluation is inclusion of the SMA/SMV relationship and the kidneys to assess the possibility of malrotation or renal pathology as the cause of the child's symptoms.

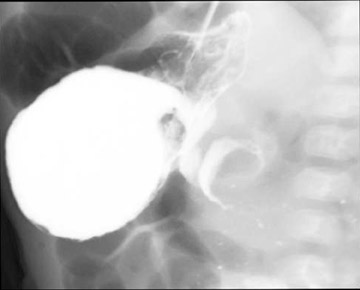

Although once the diagnostic standard for HPS, the upper GI series is now virtually never performed as an initial study for this indication; the diagnosis may be revealed during a fiuoroscopic examination for another indication, such as possible malrotation. In a positive study, one may observe "shouldering" of the hypertrophic pyloric muscle at the antrum and the string or double-track sign, representing barium squeezed between folds of mucosa pressed together by the hypertrophied muscularis layer (Figure 12). 31

Appendicitis

Luminal obstruction is the usual initial insult in appendicitis. Obstruction may be caused by a fecolith, appendicolith, lymphoid follicle, or foreign body. Lifetime risk in males is approximately 9% and in females 7%. 32 It has been estimated that 1% to 8% of children who present to the emergency department with abdominal pain will be diagnosed with appendicitis. 33,34 Appendectomy is the most common emergency surgical procedure performed in children. 26

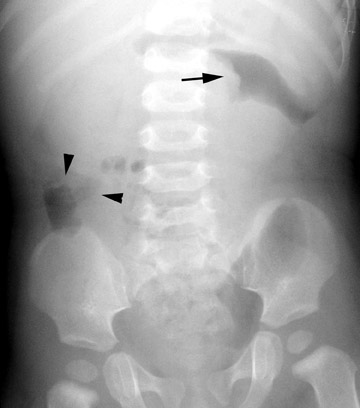

Abdominal radiographs are frequently normal in appendicitis. However, one or more of the following signs may be present: Calcified appendicolith (occurs in <10% of cases) (Figure 13); obliteration of the right psoas margin; splinting leading to a lumbar dextroscoliosis; and right lower quadrant air-fiuid levels (localized ileus). A perforated appendix may produce pneumoperitoneum.

There is significant and ongoing controversy over which imaging modality, US or CT, should be used for initial evaluation in children with suspected appendicitis. Ultrasound advantages include low cost, lack of ionization radiation, and ability to evaluate compressibility and vascularity. A sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 92% have been reported for US using meta-analysis of all studies published between 1986 and 1994. 35 Ultrasound evaluation using graded compression is performed with a high-frequency linear array transducer. Gentle pressure is applied to the right lower quadrant to compress and displace normal bowel loops. Technically adequate studies can be achieved in >95% of patients. 36 An abnormal appendix measures ≥6 mm in maximal outer diameter, is not compressible, reveals adjacent infiammatory changes, and is hyperemic with Doppler imaging. Other US findings include: Echogenic submucosa in early acute appendicitis; a target sign if the appendix is fiuidfilled (hypoechoic fiuid layer, echogenic mucosa/submucosa, and hypoechoic muscularis); an appendicolith; pericecal or periappendiceal fiuid; increased periappendiceal echogenicity (from infiamed fat); and enlarged mesenteric nodes (Figure 14).

Advantages of CT over US include: Reduced operator dependence; enhanced visualization of soft tissues, bones, gas, and fiuid; and superior evaluation for complicating phlegmon and abscess formation. CT is also superior in obese patients. Sivit et al 37 showed that CT had a significantly higher sensitivity (95% versus 78%, P = 0.009) and accuracy (94% versus 89%, P = 0.05) than that of graded compression US for the diagnosis of appendicitis in children, adolescents, and young adults. Specificity was 93% for both. CT was especially useful when the US examination was normal. 37 The optimal CT technique is controversial. The highest reported diagnostic efficacy has been with rectal contrast only and thin collimation through the lower abdomen and pelvis, with sensitivities of 97% to 100% and specificities of 94% to 98%. 37 We prefer IV contrast without oral or rectal contrast to decrease preparation time and for enhanced evaluation of infiammatory changes, complicating abscesses, and evaluation of other intra-abdominal and pelvic structures. CT features of acute appendicitis include: Appendix diameter >6 mm; appendiceal wall thickening and enhancement; an appendicolith; apical cecal thickening; periappendiceal or pericecal fat stranding; mesenteric lymphadenopathy; phlegmon or abscess (Figure 15). 37

Meckel's diverticulum

Meckel's diverticulum occurs in 2% to 3% of the population and is the most common developmental anomaly of the GI tract. 38 The diverticulum occurs at the antimesenteric border of the distal ileum and is caused by incomplete obliteration of the omphalomesenteric duct. The diverticulum often contains ectopic gastric and pancreatic mucosa. Complications include peptic ulceration with hemorrhage, intestinal obstruction from diverticular inversion, diverticulitis, and intussusception.

Conventional radiographs may reveal calcified stones in a lamellated pattern in the lower right quadrant. Meckel's diverticulum is notoriously difficult to detect with fiuoroscopy, and a barium study to evaluate for Meckel's diverticulum is usually performed only if clinical suspicion remains high after negative cross-sectional imaging.

Hemorrhage is the most frequent complication. Technetium-99m (Tc-99m) pertechnetate scintigraphy is the imaging study of choice when a child presents with GI bleeding and a Meckel's diverticulum is suspected. After IV administration of the radiotracer, ectopic gastric mucosa in the diverticulum will appear as a focus of increased activity, usually within 30 minutes of injection (Figure 16). 39 Normal activity will occur concurrently in the stomach. In children, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of Tc-99m pertechnetate scintigraphy is 85%, 95%, and 90%, respectively. 40,41 Causes of a false-positive scan include: Gastric or small intestine duplication, heterotopic gastric mucosa in an otherwise normal small intestine, and infiammatory bowel disease that causes intestinal hyperemia. 42 A false-negative scan will result if the diverticulum contains too few or no gastric mucosa.

The second most common complication is intestinal obstruction, but identifying a Meckel's diverticulum as the cause is often difficult preoperatively. The most useful radiographic finding that suggests Meckel's diverticulum as the cause of obstruction is lamellated calcification in the right lower quadrant. 43 When the diverticulum causes obstruction, it is usually secondary to inversion that causes luminal obstruction or forms an intussusception lead point.

CT is a superb modality for diagnosing bowel obstruction, but identification of a Meckel's diverticulum is often difficult. A third presentation is right lower quadrant pain and fever mimicking appendicitis. The US findings of a tubular, hyperemic structure can mimic appendicitis; however, a Meckel's diverticulum will typically be larger, have more irregular mucosal layers, and have associated anomalous vessels (Figure 17). 44

Conclusion

Gastrointestinal emergencies continue to be a frequent cause of morbidity in the pediatric population, and several diseases requiring surgical intervention can lead to mortality if not rapidly diagnosed and treated. Radiologists are at the critical front line of diagnosis for surgical decision making and, in the case of intussusception, have a vital therapeutic role as well.