The New IR Residency Is Here: Is Your Practice Ready?

Images

Interventional radiology (IR) has evolved over the past several decades as interventional radiologists continue to become more clinically minded. Newer trainees are being instilled with the mindset that IR physicians are no longer “hired guns” who perform procedures on demand, but instead are specialists in their own right who determine procedural validity, discuss therapeutic options, including medical and surgical management, and follow patients post-procedure.

This perspective reflects a significant change from the times of Charles Dotter and one that is increasingly being adopted by many institutions. Indeed, the next generation of interventional radiologists seeks to take ownership of their patients’ care.1 Over time, this mindset is expected to grow both IR and diagnostic radiology (DR) practices through increased referrals, higher-level cases, and greater volume of diagnostic imaging related to pre- and post-procedure management.

IR Training: New and Improved

The original pathway to more clinically oriented IR physicians was established in 2000 through the Diagnostic and IR Enhanced Clinical Training (DIRECT) program in 2005. The Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) has since worked tirelessly to implement a paradigm designed to train a new generation of interventional specialists.2 The IR Integrated Residency (IRIR), approved in 2014, graduated its first small group of internally transferred residents in 2018 and will graduate its first fully matched class in 2021. As of October 2020, 89 institutions offer the IRIR, demonstrating the universal acceptance this pathway has received for training IR physicians.3

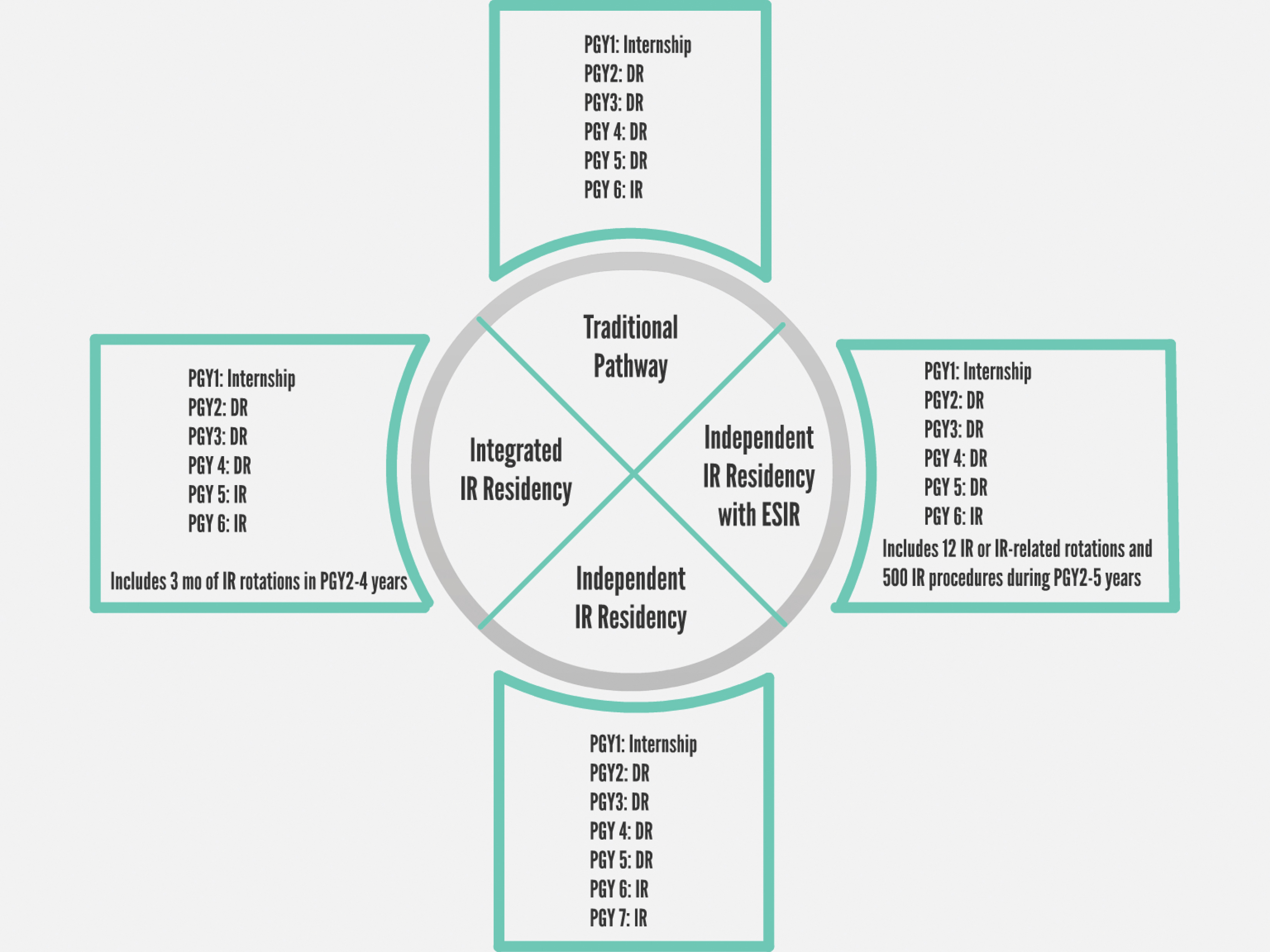

The IRIR allows medical students to match directly into IR. After completing a one-year internship, residents move on to a five-year program consisting of three years of core DR training and two years of IR clinical training. Residents who do not participate in the IRIR can transfer into IR from DR through one of two paths: the Early Specialization in IR (ESIR) route, followed by an IRIR residency; or a traditional DR residency followed by an independent IR residency. This option may take up to seven years, as compared to six years in the IRIR (Figure 1).3,4

Most current and recent IR residents and fellows believe the IRIR will improve training, a belief supported by the growing number of applicants---more than 400 for the 2019 match cycle.5,6 Nearly half of trainees surveyed by Hoffmann, et al, agreed that the traditional one-year fellowship is insufficient to prepare IR physicians for practice. Only 20 percent agreed that an IR residency would not provide adequate DR training for their future job.

The IRIR increases the amount of time trainees spend performing procedures, seeing patients in the IR clinic, rotating with consulting services, and managing critically ill patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) while also receiving DR training.7 The average trainee rotates through 3.5 non-IR clinical specialties during the postgraduate years 2 through 6, although variability exists among programs.5 Rotations through vascular surgery, ICU, oncology, and hepatobiliary surgery, for example, can increase a trainee’s comfort with caring for and performing procedures on these populations.

The increased IR training also provides further experience in the complex array of procedures performed by interventional radiologists. More time in IR and other services comes at the cost of less time in DR rotations; however, this decrease is not significantly different from other programs that offer global health or research tracks, or mini-fellowships followed by year-long fellowships, as those trainees also spend less time in DR.

Private practices will need to adapt to the more clinically oriented paradigm, paralleling other specialties such as vascular surgery and interventional cardiology. Providing sufficient clinical time to care for and treat complex IR patients is crucial to a thriving IR practice. In the near term, this may seem a detriment, as the approach initially may not generate relative value units (RVUs). On a larger scale, however, it offers an opportunity to solidify private practice contracts with hospitals. Many purely diagnostic imaging services can be performed remotely or via teleradiology, but an IR component may secure the local presence of a DR practice, as well.

Additionally, as IRs develop and build their own practices, they can generate imaging and evaluation and management (E&M) revenues. Many DR practices are being bought by larger corporations, and contracts are being sold to teleradiology, but the same cannot be said of IR practices that require boots on the ground. Maintaining an active practice that evolves with the growing clinical nature of IR will solidify a DR/IR or solo IR private practice presence in a hospital system or outpatient setting.

Private Practice Group Concerns

Hiring competitive and talented IR physicians is a must for IR section heads in an expanding physician-owned IR/DR private practice. In previous years, private practice groups knew what to expect from graduates of programs with a known training paradigm. However, since IR residency programs are producing a novel type of IR graduate, new questions are arising for private practices: Are these IR graduates ready to handle the heavier workload that goes along with many private practices? Can they provide work of similar quality from a diagnostic standpoint, even if DR is not a large percentage of their daily workload? It seems reasonable to be concerned that new IR residents may lack DR quality and efficiency.

Key to answering these questions is looking at how a program has evolved to handle the new educational needs of IR residents. Evaluating how a program has transitioned to the IR residency is important; it must continue to value the need for, and provide, high-quality diagnostic training. It must continue to mandate adequate time on valuable, high-yield diagnostic rotations while also allowing trainees to focus on their IR training. This can be vital to success in the private practice world. Unfortunately, ascertaining this information from an IR candidate can be difficult for a private practice; the onus ultimately lies on the training program to produce skilled and versatile IR residents.

Forthrightness is also important on the part of private practice groups to convey the potential diagnostic demands of group members. Informing interviewing candidates of expected diagnostic contributions enables them to decide if those expectations align with their career goals and may help to ensure their long-term job satisfaction. Many new IR trainees may be seeking a career without DR imaging responsibilities; the practice models now available—mixed private practices in academic, as well as solo IR practices—may afford these opportunities.

A final consideration for a private practice is whether it is truly ready to hire the new generation of IRs. These physicians are trained to work in environments where they are viewed as clinical specialists intimately involved in patient care. Cultivating this culture takes time and effort, which are not easily translated into traditional radiology RVU-type metrics. Providing space for the IR section to function as a highly valued clinical entity within the group is key to success.

Current IR practice not only includes reimbursement through procedural CPT codes but also through E&M codes. However, this also requires dedicated infrastructure, time, and personnel; practices that include IR must accommodate these requirements.1 This may be challenging for small private practice groups or those that are not highly specialized. However, the trend in private practice is toward sub-specialization and growth, which hopefully will allow today’s new IR specialists to function more effectively in these settings.

Recent IR Residency Graduate Concerns

New IR residents have many questions when exploring private practice opportunities: IR-only or joint IR/DR practice? Will I be permitted the time necessary to maintain the clinical nature of IR? Am I prepared to read diagnostic studies?

The answers to these questions are complicated by each practice’s unique structure, often relating to DR and call responsibilities. The graduate’s decision frequently depends on the actual or perceived DR support of IR and the time required in DR. Although DRs typically generate more RVUs, support for the clinical nature of IR is crucial for a high-functioning IR practice capable of performing more than routine biopsies and drain placements.

Building an IR practice by speaking with referring providers and hosting community educational sessions is a slow process, but it is one that will ultimately yield dividends as an RVU generator for DR and IR alike. The amount of time required on DR will be vary with practice, and newly minted IR physicians will have to decide how much time they are willing to dedicate to DR. In a joint practice, dedicated DR days helps to foster a symbiotic relationship between colleagues. They also maintain diagnostic skills in the event of changes in career or personal circumstances.

Preserving the clinical nature of IR in private practice is a challenging task that also requires educating the billing department. Proper coding and billing of non-procedural components, including inpatient and outpatient E&M billing, will help secure appropriate reimbursement. Regular consultation with the financial administration is crucial. In addition, communication with DR colleagues is vital to maintaining relationships within the group. Documenting cases and consultations permit DR colleagues to appreciate the required to care for each patient. When possible, assisting with image interpretation between IR cases fosters goodwill and a team-player reputation.

Maintaining diagnostic skills throughout the IR residency is not as difficult as it may seem. Interventional radiologists routinely read their own pre- and postprocedural imaging and practice their skills in vascular imaging and body MRI, especially with respect to oncology patients. Many programs may also provide diagnostic rotations during the PGY5 and PGY6 years in order to keep up to date on DR skills.

Neuroradiology, musculoskeletal radiology, nuclear medicine, pediatric radiology, and mammography may prove more challenging in this respect, but quality improvement conferences are a great option to catch blind spots. Most new practices will conduct short-term reviews of diagnostic studies to appropriate reading pace and level, serving as an added level of protection for a newly practicing physician.

Conclusion

Incorporating new IRIR graduates is a significant change for most private practices. But sufficient communication and support will help ensure that these physicians can continue to practice clinical IR while contributing RVUs to the practice. Graduates will require patience and perseverance to build a practice that best suits their needs and the needs of their patients, and they must also be sure to maintain the diagnostic skills necessary to meet the demands of the private practice.

References

- Marx M. IR Residency Training: Is It Appropriate for the Private Practice IR? Seminars in Interventional Radiology. 2019;36(01):035-036. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1679946

- Kaufman J. Evolution of IR Training. In: Keefe N, Haskal Z, Park AW, Angle J, eds. IR Playbook. Springer; 2018:3-6.

- Society of Interventional Radiology- Integrated IR residency. Sirweb.org. Published 2019. https://www.sirweb.org/learning-center/ir-residency/integrated/

- Marco LD, Anderson MB. The new Interventional Radiology/Diagnostic Radiology dual certificate: “higher standards, better education.” Insights into Imaging. 2016;7(1):163-165. doi:10.1007/s13244-015-0450-9.

- Hoffmann JC, Singh A, Szaflarski D, et al. Evaluating current and recent fellows’ perceptions on the interventional radiology residency: Results of a United States survey. Diag Intervent Imaging. 2018;99(1):9-14. doi:10.1016/j.diii.2017.05.006

- Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2019-12/2019_FACTS_Table_C-3.pdf. aamc.org. Published 2019. Accessed November 5, 2020.

- Mandel JE, Makary MS, Fleming JW, et al. The Integrated IR Residency Curriculum: Current State of Affairs. J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 2020;31(1):176-178. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2019.09.008

Citation

N K, J D. The New IR Residency Is Here: Is Your Practice Ready?. Appl Radiol. 2021;(2):16-18.

March 11, 2021